1286 years ago, somewhere between Tours and Poitiers in current-day France (it was called Gaul at that time, but I’ll stick to the name “France” in this article), a European army stopped a Muslim invasion into the heart of France.

The exact date is unknown, but it was probably a Saturday in October 732 A.D. A large Muslim army under Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, the governor of Muslim Spain had entered the territory of current-day France from Spain, intent on booty and on expanding Islamic rule.

Preliminaries

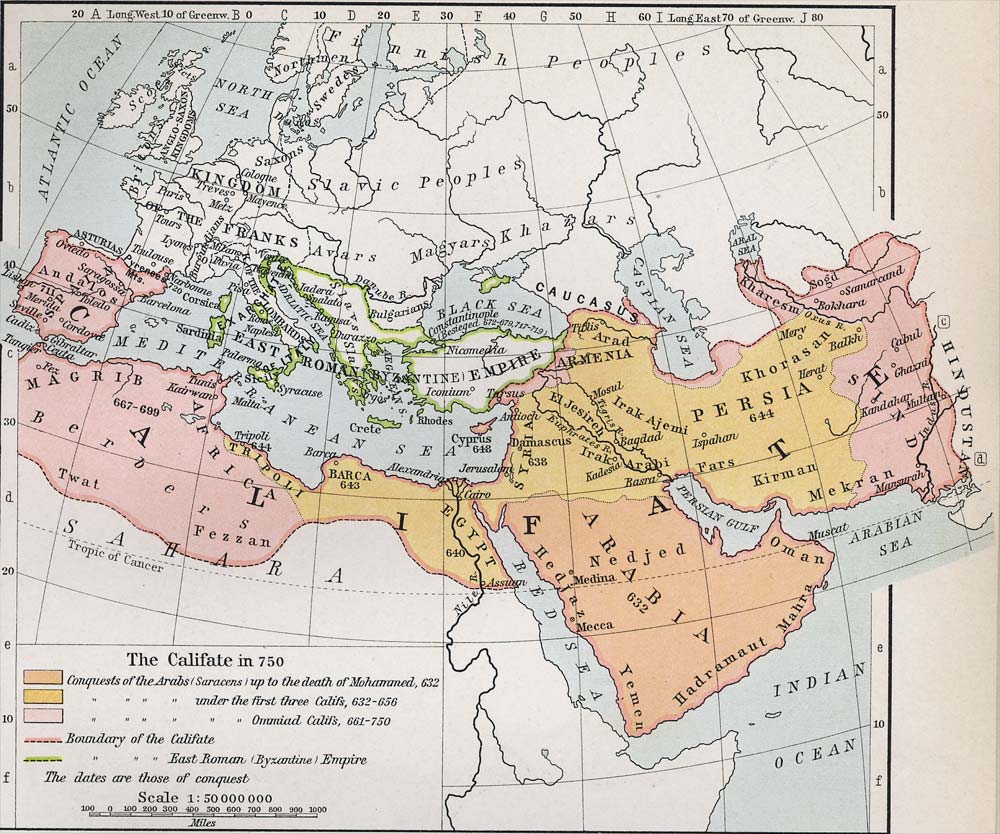

Events had followed each other quickly over the previous 21 years, since 711.

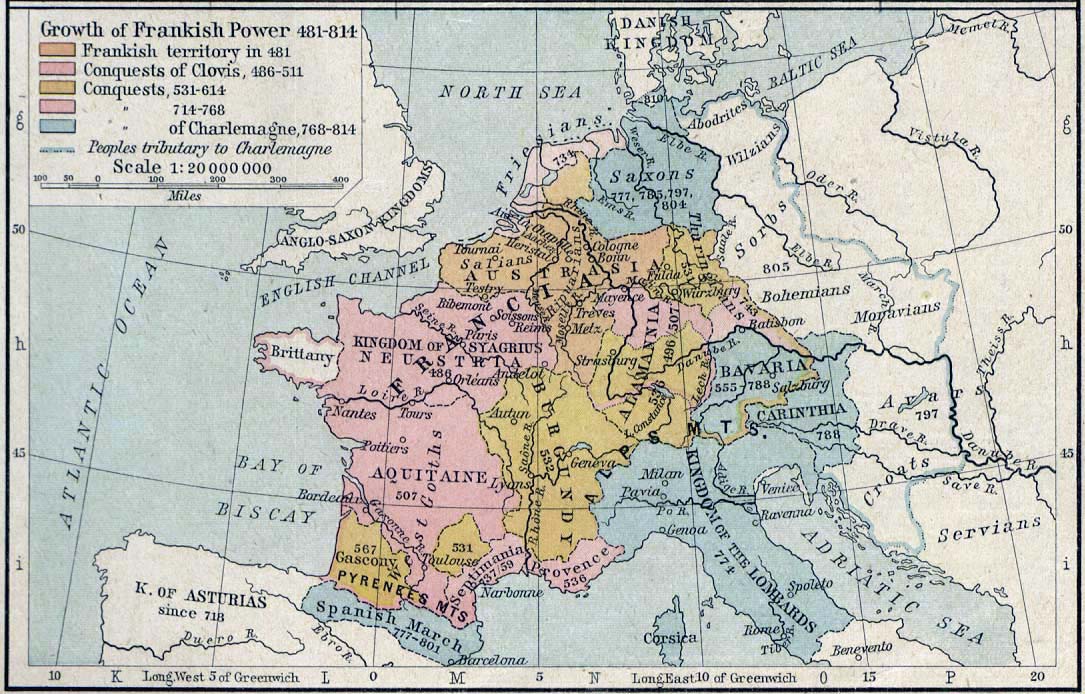

Before that time Spain was still a Christian kingdom, a domain ruled by Germanic Visigoths—who also occupied an area in Southern France called Septimania. Most of the rest of France was ruled by another Germanic tribe, the Franks.

Then, in 711, an Arab-Berber force under Tariq ibn Ziyad entered Spain from North Africa, crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. In five years, almost the whole of Spain became a province of the huge Umayyad caliphate. Soon thereafter Muslim armies started raiding Southern France. In another three years, by 720, Septimania in Southern France was also under Muslim rule. The city of Narbonne became the Muslim capital of the newly conquered Southern French territories.

Then, a setback: the governor of Umayyad Spain, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, decided to venture into Aquitaine, a large duchy with a long Atlantic coast line in South-Western France, nominally a dependency of the Frankish kingdom to its north but in practice quasi-independent. Al-Samh invaded Aquitaine in 721 and took Toulouse, the capital of the duchy, under siege. Duke Odo of Aquitaine left the city to find help. He came back with a considerable army, attacked the Muslim besiegers and beat them devastatingly. Al-Samh himself was wounded and died shortly thereafter in Narbonne.

This setback stopped the Muslim attempts to conquer Aquitaine for a time. However, the expansion of Muslim rule in Southern France continued: Béziers, Nîmes and Carcassone were all captured by 725.

Then, in 731, the recently appointed governor of Umayyad Spain, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, suppressed a revolt by one of the Muslim officials in Northern Spain. Duke Odo of Aquitaine had supported this official, and Abdul Rahman took this as an occasion to start another Muslim invasion of Aquitaine.

The invasion

The invasion started in 732. There are widely varying estimates of the size of the Muslim forces. Military historian Victor David Hanson thinks that it was probably between 20,000 and 30,000 strong. It included a large cavalry force. Plundering along the way, the Muslim army reached Bordeaux, where it encountered the forces of Duke Odo. The Duke, who 11 years before was able to beat the forces of Al-Samh, wasn’t as lucky this time: his army was thoroughly beaten by Abdul Rahman’s forces and the Duke fled north to ask Duke Charles, the maior domus for help.

Charles—who later was called Martellus or Martel, because of his hammer-like efficiency in beating his enemies—then gathered his forces to face the enemy which, plundering churches and monasteries on its way, was approaching the area between Poitiers and Tours.

The army of Charles was probably about the same size as the Muslim army. It consisted exclusively of infantry, while the Muslim army had a large contingent of heavy cavalry.

The battle

A week of maneuvering started, during which Charles kept a defensive stance. At the end, the Muslim commander, realizing that winter was approaching, and also probably that food and fodder for his army was running out, decided not to wait any longer and to attack. Charles had managed to concentrate his forces in an advantageous location, where they were screened in the front from mass cavalry attacks. They formed themselves into a square, shoulder to shoulder, protecting themselves with large shields, similarly to the phalanx formation of ancient Greeks.

The battle lasted until nightfall. Military historian Victor David Hanson, citing a contemporary chronicle, writes : The Franks

“stood one close to another” like a “wall”. “As a mass of ice, they stood firm together”. Then “with great blows of their swords,” they beat down the Arabs. The image from the contemporary chronicle is clearly one of near motionless foot soldiers, standing shoulder-to-shoulder using their spears and swords to repel repeated charges of horsemen (p. 138).

At one point during the battle a rumor spread in the Muslim army that Charles’ forces attacked their camp. To protect the slaves and other booty the Muslims plundered during their campaign, many Muslim soldiers left the battle field and hurried back to their camp. This resulted in a general withdrawal. Among the chaos Abdul Rahman was killed, and the Muslim forces left the battle field. The Franks maintained perfect discipline and didn’t follow them. Instead, they remained where they stood, expecting a new onslaught the next morning. This, however, never came: when the Franks approached the Muslim camp they found only empty tents. The enemy left and fled back to Spain.

The aftermath

Victor David Hanson estimates that maybe 10,000 Muslims were killed in the battle. The losses of the Franks were far less, maybe a tenth of that number. Also, the Muslims now lost the second governor of their Spanish province in battle with Western Europeans in slightly more than a decade.

Never again campaigned a Muslim army as far north in France as Abdul Rahman’s army did. But this didn’t mean that they stopped attempts at further raids and conquests in France. Only three years after the battle of Tours, in 735, the newly appointed governor of Muslim Spain, Uqba ibn Hajjaj attacked north alongside the Rhône valley. Muslim forces took Avignon and Arles, both on the Rhône river and about 200 km northeast from their strong point at Narbonne. The next year, in 736, the Muslims of Spain started a naval invasion, landing in Narbonne, and moving inland towards Provence beyond the Rhône river.

However, Charles, who previously had continuously been at war with other Germanic tribes, now focused, as his main target, at the Muslim encroachments in Southern France. He answered the Muslim naval invasion in the same year by re-taking Avignon, Nîmes and Arles, destroying one Muslim army at Arles in the process, and then moving on towards Narbonne, where he beat another Muslim army. He also attempted, unsuccessfully, to take the city of Narbonne.

Charles Martel died in 741 and Narbonne was left in Muslim hands. The Muslims continued large scale campaigns—for example attacking Lyon in 743—until 759, when Narbonne was taken by Charles Martel’s son, Pepin. The whole of Muslim Southern France—Septimania—was taken by the Franks by 760.

The importance of the battle of Tours

“Charles Martel’s victory at Tours saved Christian Europe” are what many people think about this event.

I believe that this overstates the importance of the battle. The Muslims were a tough enemy, not to be intimidated by a single setback, however large. This is shown by the fact that the Tours campaign followed the huge defeat they had suffered at Toulouse only 11 years earlier. Furthermore, shortly after their defeat at Tours they were ready to invade and conquer in Southern France again.

However, Muslims never again invaded or raided in Aquitaine, in the South-Western part of France, moving their attacks further to the East. Furthermore, and most importantly, the battle was indeed a turning point in that it seems to have turned Charles Martel’s attention at defeating the Muslims in Southern France.

The result of this was not only to stop further Muslim conquests in Southern France but, ultimately, a rollback of their conquests there. After 40 years of occupying Narbonne, they had to give it up and leave Southern France altogether.

But it was not easy; a determined, focused, prolonged effort was necessary, not just by the brilliant military leader Charles Martel but also by his son Pepin later, to free Southern France from Muslim occupation.

What would have happened if Charles had lost the battle of Tours? In spite of the great fighting ability of the Frankish soldiers, who “as a mass of ice, stood firm together”, this was not an impossibility. During the Norman invasion of England in 1066, at the battle of Hastings, the anglo-saxon forces of king Harold were also formed in a “wall of shields” and faced Norman cavalry attacking them. Though the anglo-saxons at Hastings were not as disciplined as the Frankish soldiers of Charles Martel at Tours, the battle was ultimately decided in favor of the Normans when king Harold was killed, maybe by an arrow shot into his eye.

Charles could have been killed at Tours in a similar manner, by a Muslim arrow. This would have left his army leaderless and the Muslims would probably have destroyed it, opening their way towards Tours and further towards the North. It is doubtful that the weak, “do-nothing kings” (rois fainéants) of the Frankish Merovingian dynasty would have been able to stop the Muslims, after their most able general was defeated and killed. The Muslims would have been able to continue towards the North if they had wanted to.

But even if they had decided not to continue much further, they would have conquered a large territory south of Tours where, having won a battle against the Duke of Aquitaine at Bordeaux a few months earlier, they didn’t have any important undefeated enemy. Thus, a defeat of the Franks at Tours could easily have resulted at least in winning another large territory in South-Western France, in addition to their conquests in Southern France. This then could have given them a stepping board to later conquests in the North.

Some historians play down the possible consequences of such a victory by the Muslim army at Tours. They say that the campaign by Abd er-Rahman in 732 was nothing more than a large-scale booty gathering expedition. Winning the battle would have allowed the Muslims to rob the treasures of the monastery of St-Martin at Tours, but then they presumably would have headed home with the booty collected.

Whether correct or not, this argument fits well into the politically correct atmosphere of our time: the Muslims were no real danger for European Christianity: they only wanted booty and not to conquer Europe. Thus, this implies that there was no real need to be afraid of them.

However, the argument is wrong—and not just because of its political correctness. There is no reason why the Muslims would not have made their conquest in Aquitaine permanent, if they had had the chance, just as they did everywhere else, both before and afterwards: in Southern France around Narbonne and later in Southern Italy and in Sicily—where they remained for some 260 years until the Normans finally expelled them. It was the same pattern as followed in many other places invaded by Muslims: after initial successful raids Muslims stayed either permanently or for long periods of time, until they were expelled, often under great difficulties. For example, Hugh Kennedy writes about the times of the battle of Tours:

Until this point the Muslim armies had raided far and wide in France, even if they had not made any permanent conquests. As the people of Central Asia were finding out at exactly this time, Arab raids could be a prelude to more lasting conquests (p. 320).

One thing seems certain: a lasting Muslim occupation of Aquitaine would have made regaining territory occupied by Muslims in France and Spain far more difficult and time consuming.

Thus, my conclusion is this: the Muslim invasion led by Abdul Rahman was indeed very dangerous for Europe. Whether that danger was going to be realized depended on the outcome of the battle at Tours. Winning that battle was important because losing it would have changed European history decisively. However, winning the battle alone wasn’t enough to ban the Muslim danger in Southern France. Further determined effort was needed to achieve that. This was helped by the fact that the confrontation with Muslims seems to have focused Charles Martel’s mind on the Muslim danger. This led Charles—and later his son Pepin—to maintain the pressure, until, in 760, almost 30 years after the battle of Tours, all Muslim occupation forces were eventually evicted from France.