Islamic conquests started already during the life of the prophet Mohammed and they greatly intensified after his death in 632 A.D. Within 20 years large parts of the Middle East — including the Persian Empire and territories of the Byzantine Empire in Syria, Palestine and Egypt — were conquered, and within 80 years the whole of North Africa and Spain were under Islamic rule.

Initially, the 7th century Islamic conquerors had little regard for science or philosophy. However, within about 150 years after the initial Islamic conquests, during the Abbasid caliphate (750–1258), Islamic countries became world leaders in scientific inquiry (Huff, 2017, p. 59).

To have an idea about how remarkable this was, one can compare the conquest of the West Roman empire by Germanic tribes and the dire state of philosophy and science in the Roman West for hundreds of years afterwards (Grant, 2011, p. 17).

The translations

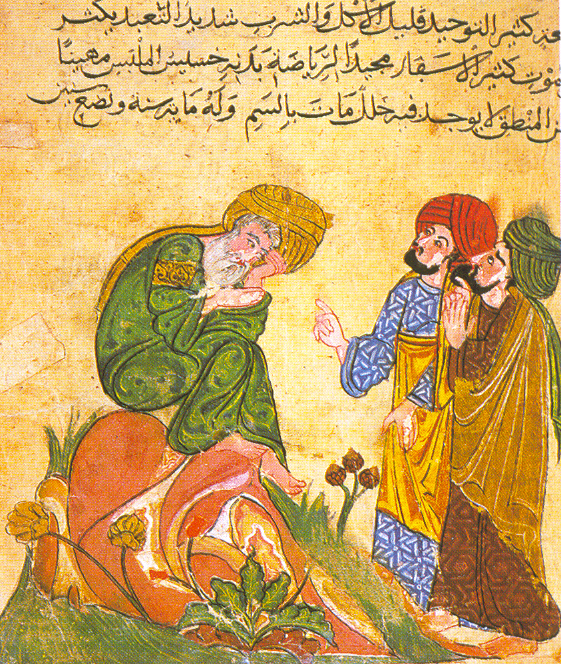

One decisive advantage the Arabs had was the availability of the huge scientific heritage of Greek and Greco-Roman philosophy and science in libraries and monasteries in the conquered Middle East. The conquering Arabs did not speak Greek but large populations of Christians—Nestorians, Jacobites, Maronites and others—lived in the Middle East who understood or spoke Greek and were able to translate the works of classical authors first from Greek into Syriac and later from Greek and Syriac to Arabic. The most famous of the translators was Hunayn ibn Ishaq, a Nestorian Christian who worked during the reign of caliph al-Mamun in the 9th century.

Although there was a similar translation activity already during the Umayyad caliphate preceding the Abbasid era (Gutas, 1998, p. 23), the large scale translation effort started at the beginning of the Abbasid caliphate in the mid-8th century and was supported not only by rulers like the caliphs Harun al-Rashid and his son, al-Mamun, but also by other members of the elite in the caliphate. It was an expensive effort. Dimitri Gutas writes in his book Greek thought, Arabic culture:

The sons of Musa ibn Sakir [a protégé of caliph al-Mamun] … used to pay monthly 500 dinars to Hunayn, Hubays and Tabit ibn-Qurra for “full time translation”.

Gutas, 1998, p. 133

To put this into perspective, in 9th century Baghdad foot soldiers earned 1 dinar a month, cavalry soldiers 2 dinars a month, a private teacher of children of the caliph 25 dinars a month, market supervisors 100 dinars a month, and physicians 500 dinars a month.

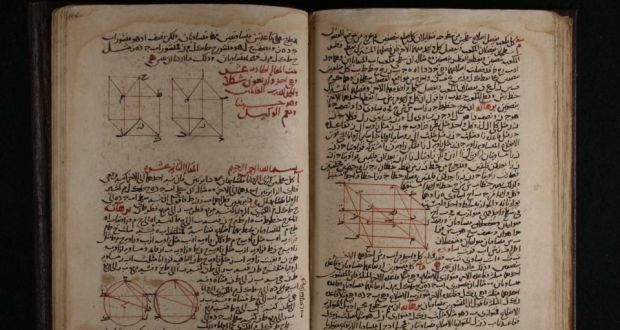

Works of Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy, Euclid, and of many other classical authors were translated. There was an intense effort to find original Greek manuscripts in the Islamic empire, and if they couldn’t be found, sometimes they were acquired from the Byzantine Empire.

The classical Greek authors have been seen with a degree of suspicion and their works were regarded as the “foreign sciences”, in contrast to the “Islamic sciences” (which included the “science” of interpreting the Quran and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, the Hadiths).

Why were the translations supported by the Arabs?

Why then would a society as intensely religious as Muslim society support a large scale effort aimed at translating such “foreign” works? One part of the answer could be that initially the potential “danger” of these works for the Islamic religion was not clearly perceived. Another part of the answer is that in early Islamic thinking during the the clear cut fronts of later periods were not yet present. This allowed the entry of ideas from different sources, e.g. Christianity, and also from Greek philosophy and science. Still, the antipathy against the “foreign sciences” grew in time and it had to be overcome—and not only temporarily, but for about 250 years, during which, as David Lindberg writes,

almost all of the scientific works of the classical tradition as we know today [were translated].

Lindberg, 2007, p. 170

So what was the motivation of the Arabs in keeping such an expensive, long term translation effort going and in learning about the “foreign” works of ancient pagan Greek philosophers and scientists? There doesn’t seem to be any hard evidence pointing to specific reasons, and thus, most of the explanations are not much more than more or less plausible speculations.

Muslim society was not monolithic: it contained different groups with partially different interests. The leaders and elites wanted to have a good life, and some types of the knowledge of ancient Greek authors — e.g. medical knowledge — were seen as useful for that. Sometimes these elites themselves became interested in Greek science and philosophy, maybe as a pastime or a mental challenge, and thus supported the translation effort and philosophic-scientific activity.

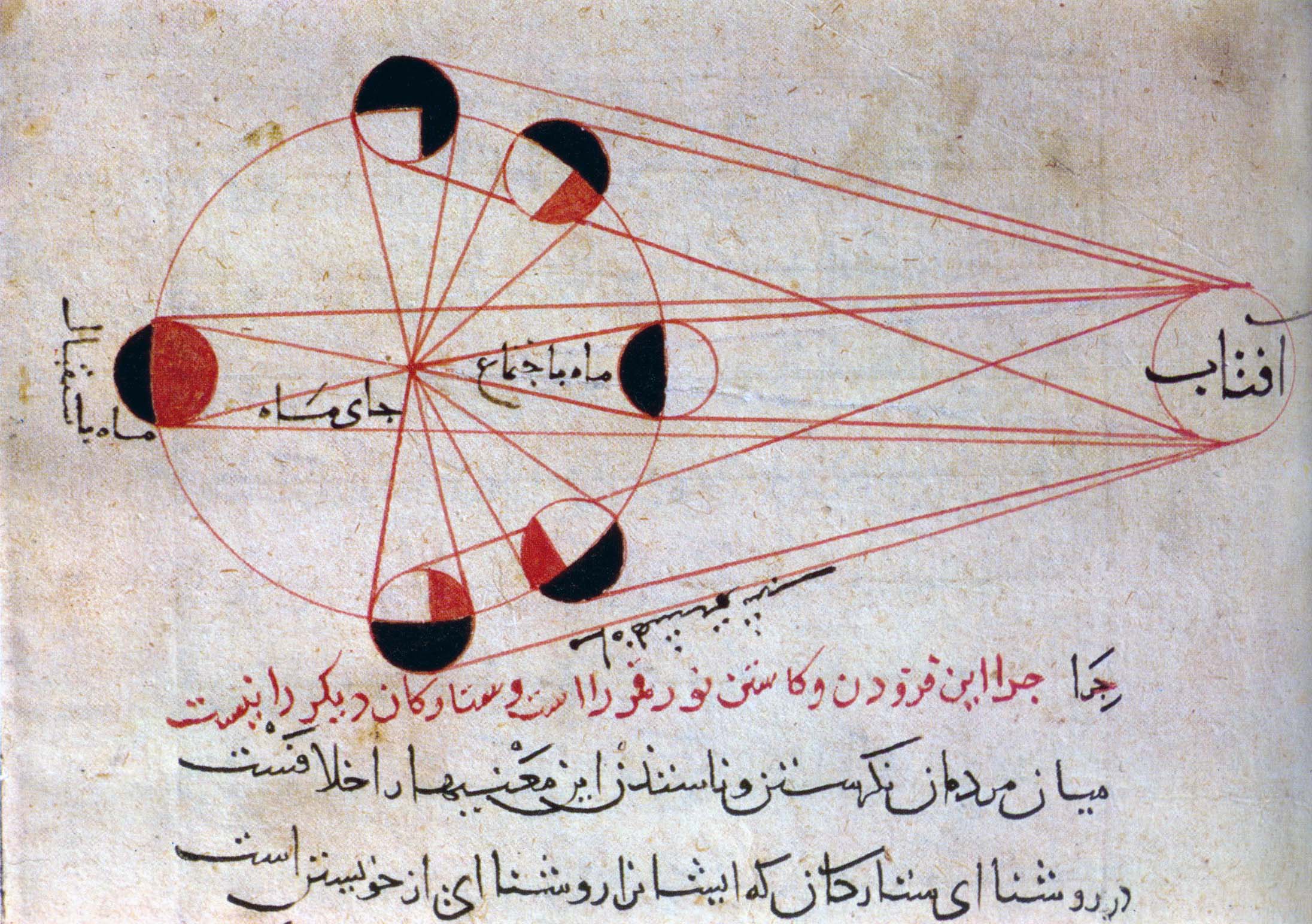

Other sciences, like mathematics and astronomy had also practical implications, in determining the time of prayer, the beginning of Ramadan and Muslim prayer times (Lindberg, 2007, p. 170). Classical works on logic were also seen by some Muslim theologians as useful in arguing theological points.

Photograph: copyright the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library

Furthermore, like at many other times in history, the conquering culture and the more sophisticated culture of the conquered started to merge. The conquerors “appropriated” parts of the conquered culture, and the conquered adapted to the new situation. The area of current day Iraq, where the Abbasids set up the center of their caliphate, had been part of Persia, where also many Nestorian and monophysite Christians lived. These Christians had a high culture and translated, already before the Arab conquest, many classical Greek works into their language, Syriac. Persian rulers had been patrons of learning and had been supporting these Christians. When the Arabs came, they would have been impressed by the sophistication of the Persians, and would have tried to emulate it, maybe also to increase the legitimacy of their rule (Lindberg, 2007, p. 170). This might have been another part of the explanation of their support for the translation effort, this time from Syriac to Arabic, but also directly from Greek to Arabic.

The Abbasids also employed some high-standing officials of non-Arab origin. Khalid Barmak and his successors, the Barmakids, who, before converting to Islam, were originally Zoroastrians (or Buddhists), are one example of such officials. The Barmakids became ministers and viziers of five of the Abbasid caliphs, starting with al-Mansur. They supported arts, architecture, science and philosophy.

The influence [of the Barmak family] was a Hellenizing one; for the family had extensive knowledge of what Greek civilization had to offer.

Young, Latham, & Serjeant, 1990, p. 478

A further motivation for supporting science could have been a political one. The Abbasids tried to distance themselves from the preceding Umayyad dynasty who supported theological movements which emphasized predestination, i.e. the idea that Allah determined the fate of every human being. A person doesn’t have free will and can’t escape his fate, no matter what he does in life and what decisions he makes. The Umayyads liked this idea because they saw it as a support for the view that their rule as caliphs was predestined by Allah.

The Abbasids, when they took over in 750 A.D., stopped supporting these movements, maybe as a way of differentiating themselves from the Umayyads. Instead, they started supporting opposing qadarite movements which emphasized the free will of people and their ability to decide whether to live a pious life or to sin. One of these movements was the theological school of the Mu’tazilites. This school was influenced by classical Greek knowledge, in particular of logic. Thus, Greek knowledge received an entry into Muslim intellectual life via politics and theology.

One additional explanation could be that the translation movement was a dynamic process, involving positive feedback: the exposure to Greek science and philosophy became a self-sustaining and self-reinforcing process. The starting point might have been translating Greek works of practical relevance, like works on medicine. However, most of these ancient works had references to other works and philosophical connotations. In order to understand those references and connotations, other works explaining them needed to be translated. Those works had references to other philosophical works, thus, in order to fully understand them, translations of those other works became also necessary. All these works began to be debated among scholars who also wrote commentaries about them, arousing interest in further translations. And so on.

The Abbasid caliphate: a world center of intellectual activity

As a result, Baghdad under the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs became a center of learning and the Islamic “Golden Age” ensued. Muslim scholars like al-Khwarizmi, Ibn al-Haytham (called Alhazen in later Latin writing) and al-Biruni made discoveries in mathematics, optics, biology and astronomy.

Often, the work of these scientists had practical benefits, for example in the health professions: they were employed as medical doctors, providing medical assistance to Muslim rulers. Philosophically inclined scholars like al-Kindi, al-Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) debated about theories of Aristotle and alternative theories of the universe.

Literature

Grant, E. (2011). The Foundation of Modern Science in the Middle Ages. Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gutas, D. (1998). Greek thought, Arabic culture. New York: Routledge.

Huff, T. E. (2017). The Rise of Early Modern Science. Islam, China and the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lindberg, D. C. (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science. The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450. Second Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Young, M. J. L., Latham, J. D. & Serjeant, R. B. Eds. (1990). Religion, Learning and Science in the ‘Abbasid Period (The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

To be continued.

Be the first to comment on "How science lived in Europe and died in Islam, Part 2: The rise of philosophy and science in Islam"