The King is a movie on Netflix, directed by David Michôd. It follows the life of Henry V, king of England, from his days as Prince of Wales – prince “Hal” – shortly before the death of his father, Henry IV, until his marrying Princess Catherine, the daughter of the French king Charles VI. Dramatic scenes follow one another, with the young prince fighting an opponent, embarking on campaign in France, fighting in the battle of Agincourt and even killing a traitorous courtier with his own hands.

The film is popular on IMDB: currently (December 2019) it has earned 7.3 stars. Many user comments are very positive, but some are very critical, often because they decry the many historical inaccuracies in the movie.

Some professional critics are also very critical. For example, Nate Jones in Vulture compares the Shakespearean dialogues, side by side, with the dialogues in the movie and comes to this conclusion: The film

borrowed most of the plot, characters, and big moments from Shakespeare’s trio of plays about the monarch, but chose to jettison the Bard’s famous verse in favor of dialogue of their own creation … Besides the language, they’ve also changed the fates of a few supporting players, and given the story new themes. Timothée Chalamet’s Hal is now a noble pacifist who disdains war and imperialism, which is kind of like turning Romeo into an incel.

David Sims writes this on Atlantic:

The King is a bizarre mix of fact and fiction that sacrifices the realism Michôd is trying to convey, as well as the humor and charm of Shakespeare’s plays.

We suggest that The King can be described as a mixture of four elements:

- Accurate history

- Fake history: inventions by the two script writes, often replacing well-documented historical events. In addition, important events are sometimes glossed over.

- PC history: “politically correct” themes and moralizing introduced into the script

- Shakespearean connections: dialogues and events in Shakespeare’s plays Henry IV and Henry V heavily edited and modified for the movie – often distorted into the opposite of what Shakespeare wrote.

In what follows, we shall analyze these four elements in detail. As a source to the historical background we shall heavily rely on two books by Juliet Barker on the period: Agincourt and Conquest (see the Literature section at the end).

Accurate history

The general outline of the story of Henry V, as depicted in The King, is historically correct.

Prince Henry was indeed the son of King Henry IV, with whom he had a somewhat complicated relationship.

There was indeed a conflict between Henry “Hotspur” Percy (and his uncle, Thomas Percy) and King Henry IV, which achieved its climax at the battle of Shrewsbury, in which “Hotspur” died.

Prince Henry did follow his father on the throne, becoming King Henry V. He gathered an army and invaded France in 1415, first besieging the French harbor town of Harfleur. As shown in the movie, he did use impressive siege catapults – trebuchets.

This was followed by a long march toward the Northeast.

The army of Henry V and the French army met on a field near the village Agincourt (or Azincourt) on 25 October 1415. It rained heavily the night before the battle. On the day of the battle the English deployed their men-at-arms in the middle and a much larger number of longbow-armed archers on both sides of their thin line. The French attacked, all the while being shot at by the archers of the English army. A bloody melee ensued when the French met the line of the English men-at-arms. Henry V actively participated in the fight.

The French lost the battle. Later, the French king Charles VI agreed to the marriage between his daughter Catherine and Henry V.

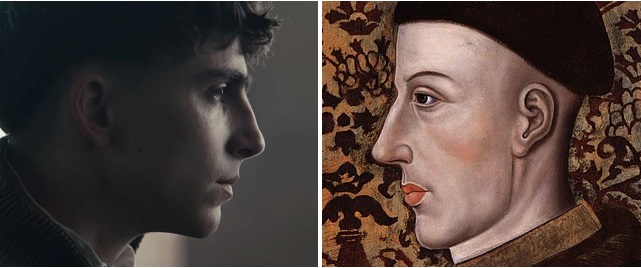

One additional thing that was correct in the movie: the facial features of Timothée Chalamet, the actor playing Henry V in the movie, and of the real Henry V – as depicted in paintings – are remarkably similar.

Fake history

While the general outline of the movie is historically correct, there is a large number of historical inaccuracies in the movie inserted into it by the script writers.

The prince

In the movie, Henry, before he became king, is depicted as leading the life of a whoring vagabond, together with his mate Falstaff. This is based on comments written much later (and picked up by Shakespeare), but there is almost no contemporary evidence for it. As Juliet Barker writes,

the only contemporary hint of even the slightest misconduct is a comment by his friend Richard Courtenay, Bishop of Norwich, that he believed that Henry had been chaste since he had become king.

Barker (2007), p. 41

According to the movie, King Henry IV is so disappointed in his wayward first born son that he removes his right to inherit the English throne, and gives this right to his brother, Thomas. In reality, despite tensions between King Henry IV and his son Prince Henry, the king has never attempted to do such a thing.

In addition to disinheriting Prince Henry, the movie’s script writers make the king assign the task of defeating the rebellion of the Percys to Thomas who then prepares to do battle against the rebels at Shrewsbury (until Prince Henry unexpectedly appears on the scene). This is pure invention by the script writers: it can be found neither in Shakespeare’s play King Henry IV, Part 1, nor in historical reality. Instead, the English army at the battle of Shrewsbury was commanded by King Henry IV and by Prince Henry.

The fight between Prince Henry and Henry “Hotspur” Percy at Shrewsbury, as shown in the movie, did originate in Shakespeare’s play Henry IV, Part 1. This fight, in which Percy was killed by the Prince, did not take place in reality; instead, “Hotspur” died in battle, maybe killed by an arrow which hit his face.

At the real battle, Prince Henry was also hit by an arrow in his face. His surgeon was able to remove the arrow later and thus saved his life. In the movie, the wound left by the arrow is shown on the left cheek of Henry, but in reality the arrow apparently hit his face near to his nose. The wound is small, appears suddenly on Henry’s face after the Shrewsbury fight scene, and remains there during the rest of the movie. It remains unexplained and mysterious – all the more so as, according to the movie, the fight between Henry and “Hotspur” supposed to have avoided a battle (and thus no arrows would have been shot).

The campaign in France

In the movie, after having been crowned king of England, Henry asks his old mate Sir John Falstaff to join him on his campaign to France. Falstaff is at that point a drunkard and apparently a thief, who owes money to an inn-keeper. But this didn’t keep the script writers from making Henry choose him as the marshal of his army, after Falstaff agrees to accompany him to France.

Nothing like this took place, either in reality or even in a play by Shakespeare who invented Falstaff’s character.

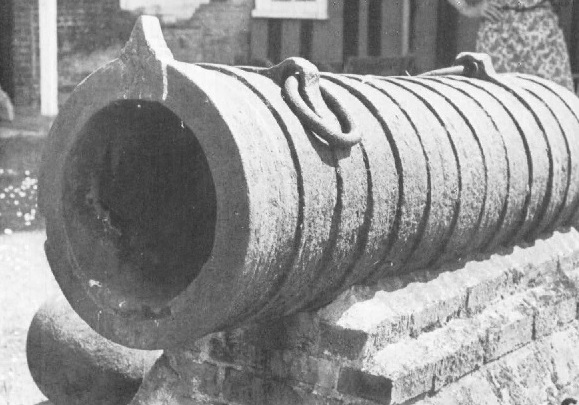

The siege of Harfleur is depicted as a rather low key affair. In reality, it took several weeks for the English to take the town. The movie shows impressive catapults used during the siege, but it omits showing the guns which were also used, some of them shooting huge stones against the walls. There was a continuous bombardment by these guns, gradually crumbling the fortifications of the town (Barker, 2007, p. 183).

From “The Boxted Bombard” by Howard L. Blackmore, in The Antiquities Journal.

The English also attempted to dig mines under the town walls, with the aim of making them collapse. Towards the end of the siege there was also an all-out-assault at the town’s fortifications by the English, which probably convinced the town to surrender a few days later. Another important event was an outbreak of dysentery among the English troops, killing or making sick many of them. Juliet Barker estimates that between 10 and 20 percent of Henry’s army was killed by the disease and at least 1693 were invalided back home to England (Barker, 2007, p. 213 – 215). This was a big loss for an army of about 12,000.

None of this – except for the catapults – is shown in the movie. The whole Harfleur episode lasts about 4 minutes in the movie – most of it spent on showing the operation of the catapults in some detail. This in a movie which spends many minutes on long rambling dialogues, for example between Henry and Falstaff when the king tries to convince Falstaff to join him in his campaign against France.

After Harfleur’s surrender, Henry is bizarrely joined by the Dauphin, the heir apparent to the throne of France and the villain of the movie, who insults Henry, and later kills one of the boy servants of his army. None of this, of course, took place in reality.

By the way: the real Dauphin at that time was about 18 years old. Compare this to the movie’s Dauphin, played by Robert Pattinson, who, at the time of the movie’s production in 2019, was 33 years old.

Then begins a long march through Northern France, in the direction of Calais. Soon, a French army is gathered, shadowing the English army on its way. But, in the movie, the English don’t seem to know any of that. When the army arrives at the field near Agincourt, the knight sent to see what lies beyond a hill looks startled to see the French camp there. (But then again, maybe the knight was startled only by the size of the French camp and not by its presence).

Battle preparations at Agincourt

The English army sets up camp as well. The next day, after a night of rain, the two armies prepare for battle. Then, suddenly an absurd scene (of which many more will follow during the following minutes of the movie): Henry visits in person the commander of the French forces who is none other than – the Dauphin. Henry suggests a one-on-one fight between the two of them, which the Dauphin rejects.

The idea that the Dauphin led the French army at Agincourt originates in Shakespeare’s play Henry V. The meeting between Henry and the Dauphin at Agincourt is, on the other hand, purely a product of the script writers imagination – it exists neither in Shakespeare’s play, nor did it take place in reality.

In reality, the Dauphin didn’t take part in this battle at all; he was at this point about 100 miles (155 km) away in Rouen, together with his father, the French king Charles VI. The leadership of the French army was divided among several commanders, like Jehan le Meingre (Boucicaut), Marshal of France, Charles d’Albret, the Constable of France and the Duke of Orleans.

The battle at Agincourt

Then the battle starts. According to the movie, a decision is made by the English to goad the French into the battle by a feigned English attack. Falstaff insists to lead this attack. Part of the English middle thus starts moving forward under his command. The rest of the middle – and the archers on the wings – are staying put, as shown in the below picture.

At the same time, king Henry, together with another part of his forces, hides in the forest on the side of the field, with the idea to attack the French from the side when they are engaged in fighting Falstaff’s troops.

Not much is true in this messy re-writing of history.

In reality, no separate part of he English middle moved forward – certainly not under the command of a non-existent Falstaff. Also, nobody – least of all the king – was hiding in the surrounding forest. The English army was drawn up in a single line on the battle field, with the men-at-arms in the middle and the archers on the wings. King Henry was in the middle with the men-at-arms.

The archers were ordered to drive forward-directed sharpened stakes into the ground, with the idea to stop an expected cavalry attack by the French against them. This salient and important part of the English battle preparation was not shown in the movie at all.

Then, for several hours, neither of the armies moved. At one point, Henry ordered the whole line – both the middle and the wings – to move forward some distance. The archers had to pull their stakes out, and drive them into the ground again in the new position.

In the movie, as soon as Falstaff’s troops start moving forward, the French mounted men-at-arms attack them. Immediately, the English archers start shooting at the attacking French, causing havoc among them. Then, having lost all of their horses, the French cavalry morphs into a crowd of men-at-arms on foot. They start fighting with the English men-at-arms in the middle. At the end there are so many of them on the field that they can hardly lift their arms and use their weapons.

The reality was different, again: the initial French attack was not a single cavalry attack. Instead, it was a three-pronged effort. The French vanguard, the main force, containing only men-at-arms on foot, was in the middle. The French cavalry – a relatively small force of a few hundred mounted men-at-arms altogether – was positioned on both sides of the vanguard (Barker, 2007, p. 292). The idea was that the cavalry overwhelms the archers while the main force, the men-at-arms in the vanguard, destroys the English middle.

In the real battle, the cavalry force of the French was defeated and dispersed by the English archers whom they attacked. Many of them left the field without taking part in the rest of the battle. It was not this small, now mostly dismounted, force that attacked the larger English forces in the middle but the main force of the French, the thousands of men-at-arms of the vanguard on foot who, parallel with the cavalry attack, walked towards the English middle in the deep mud, while also being shot at by the English archers.

The mud on the ground played an important role in the real battle, also shown to dramatic effect in the movie. In the real battle it heavily hindered the French men-at-arms while walking towards the English line. Juliet Barker describes the condition of the ground like this:

The fields where the battle was to take place was newly ploughed and sown with winter cerials. The soil was … the thick, heavy clay of the Somme … turning into a mud-bath.

Barker (2007), p. 269-270

The already ploughed field was soon so churned up by the thousands of human and horse feet that the men-at-arms had to walk in “mud up to their knees” (Barker, 2007, p. 293).

In the movie the field of the battle is not “newly ploughed”. Instead, it is covered with grass (see the picture above). Thus, it becomes somewhat of a mystery where all the mud that is shown during the battle comes from.

At one point in the movie, in one of the most ridiculous and cringeworthy scenes of it, the English force hiding in the forest runs out to attack the French from the side. King Henry, in his armor but without a helmet, armed only with a war hammer, runs in the front, fast as a rabbit.

He throws himself into the fight without any apparent protection by bodyguards.

In reality, as described above, the king was in the middle of the English battle line, throughout the whole battle.

The final absurdity in the movie’s depiction of the battle is when, towards the end of it, the Dauphin appears and challenges king Henry to a fight. The Dauphin falls in the mud, can’t get up, and is killed by Henry’s soldiers at his command. Needless to say, nothing like this happened, either in Shakespeare’s play Henry V or in reality. As already mentioned, the real Dauphin was not present at Agincourt (and, in fact, he died in Paris a few weeks after the battle, possibly from dysentery).

The aftermath of the battle

After the battle the movie shows the English army, together with king Henry, marching in the French country side again. Their goal becomes clear in the next scene when king Henry meets the French king Charles VI who offers not only his “surrender” but also the hand of his daughter, Catherine, in marriage to Henry.

Part of this story is true: marriage between Henry and Catherine was indeed arranged, and they did marry. Except, this happened almost five years after the battle of Agincourt, in 1420, and not more or less immediately after the battle, as the movie suggests. Also, this marriage arrangement wasn’t made in an almost jovial conversation with the French king but was part of the Treaty of Troyes, which, in turn, was the result of months-long negotiations (Barker, 2009, p. 28-29).

The Treaty contained another important clause: Henry became the heir to the French throne. Becoming the king of France – the title which he had believed belonged him rightfully – had been the main motivation behind Henry’s campaigns in France. But there is no mention of this outcome in the movie at all (except maybe as a hint in the unspecified “surrender” by the French king). Instead, we are treated to cryptic words from the French king about the importance of family for kings.

PC history

Part of the historical inaccuracies are anachronisms of a particular kind: smuggling into the script “politically correct” (PC) topics and moralizing.

One of these is a pacifistic attitude that Henry displays again and again in the movie. He wants to solve conflicts peacefully, both with internal and external opponents, causing as little bloodshed as possible. One example is the exchange at Shrewsbury between himself and his brother Thomas who is preparing for the battle against the rebellious Percys:

Thomas: Why are you here?

Henry: I will not allow this havoc to transpire. I’ve come to see it stopped.

Thomas: This is my battle.

Henry: If I have my way, there will be no battle.

Henry then sends a message to the Percys that he is prepared to have a one-on-one fight with “Hotspur” Percy, instead of a battle.

On his coronation as king of England, the French Dauphin sends him a tennis ball as a present which his advisers see as an insult. In contrast, Henry shows an understanding for the humiliation and even excuses it:

William: The ball is an insult to you and to your kingdom. You must respond.

Henry: Remember where, as prince, I whiled and how I spent my days? … Drinking, clowning. So is there not some truth in this jest?

After his coronation he says about the “civil strife” which affected the reign of his father, Henry IV: “This strife must end. And it will end. By conciliation”.

Then, when the Archbishop of Canterbury emphasizes the need to go to war against France to enforce the English claim to the French throne, Henry ridicules the arguments of the Archbishop. In that same exchange he also rejects the idea of possible crusades to the Holy Land.

And so on.

Later, of course, he’ll attack France. But, according to the movie, he does this reluctantly, and merely because he is tricked into that war by the scheming of his pro-war advisers.

As often with political correctness, there is a kernel of truth in all this. Henry was indeed a wise ruler, who managed to disarm internal enemies with conciliation and magnanimity (Barker, 2007, p. 41-42). But, depicting him as a person who tolerated insults in a self-deprecating manner is complete nonsense. He was very conscious of the prestige of his office as king:

In his own mind there was no question but that he was divinely appointed to rule and … he insisted on the dignity due not to himself, but to his office.

Barker (2007), p. 39

Nor is there any truth in Henry questioning or ridiculing the English claim to the French throne or him having to be tricked into a war with France.

On the contrary: already in 1413, in the year of his crowning to king of England, and two years before the Agincourt campaign, he stated the claims of the English to the French throne in negotiations with the French (Barker, 2007, p. 63).

And as for his advisers tricking him into war with France, exactly the opposite is true:

At some point in the spring of 1414, he called a meeting of the great council of the realm at Westminster to discuss and approve a resolution to go to war. Far from slavishly backing the idea, the lords of the great council delivered something of a reproof to the king … They urged him to negotiate further, to moderate his claims …

Barker (2007), p. 67

Essentially, the movie turns history upside down, making a pacifistic, internally torn individual out of one of England’s most warlike king.

Another example of anachronistic, cringeworthy “political correctness” in the movie is Catherine, the daughter of the French king, who is turned into a bit of a feminist by the script writers:

Catherine: I will not submit to you. You must earn my respect.

Henry: I understand that.

Of course he does. We would not expect any other answer from the king Henry of this movie.

Shakespearean connections

Many of the themes of the movie originate from Shakespeare’s plays about Henry’s life. However, they are so distorted and so heavily laced with stories invented by the script writers of the movie that the connection to Shakespeare often becomes almost unrecognizable.

For example, according to the movie, Henry’s brother Thomas prepares for “his” battle at Shrewsbury, when Henry intervenes and kills “Hotspur”, evoking an angry, resentful response from Thomas.

In Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1, a brother of Henry is indeed present at Shrewsbury. However, it is John of Lancaster, the third son of king Henry IV, and not Thomas. There is no conflict between Henry and John, on the contrary:

Prince Henry

By God, thou hast deceived me, Lancaster;

I did not think thee lord of such a spirit:

Before, I loved thee as a brother, John;

But now, I do respect thee as my soul.

Also, in Shakespeare’s play, the battle at Shrewsbury was not “John’s battle” (and certainly not Thomas’s, the brother who is absent at the battle). Instead, the king’s forces were led by king Henry IV himself (who is absent in the movie’s Shrewsbury episode).

Another example is Falstaff, an imaginary character who appears in Shakespeare’s plays Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2. He is maybe based on the real life figure of Sir John Oldcastle, a previous friend of Henry.

The movie introduces Falstaff early on, playing a similar role in the first part of the movie as he plays in Shakespeare: a bohemian, somewhat seedy character.

But then, the script writers seem to be desperate to continue using this character during the Agincourt campaign, maybe because he appears as the only real friend of Henry, and this gives a little human touch to Henry’s grim figure amidst all the cruelty and hardship of that campaign. So, they make the king ask Falstaff to serve as his marshal during the upcoming campaign. It remains a mystery what the king thinks would qualify this character to take on that important role.

Shakespeare was clearly wiser than the script writers of The King: Falstaff doesn’t even appear in Henry V, the last play of his trilogy about Henry, which describes the Agincourt campaign.

Maybe the script writers were having Oldcastle, the real-life “Falstaff”, in mind? That doesn’t fit either: Oldcastle did not participate in Henry’s campaign in France. He, in fact, became a Lollard who in 1414, one year before the Agincourt campaign, led a rebellion against the king, and was later executed for heresy.

A third example of a Shakespearean theme used in the movie is the tennis-ball incident: the tennis-ball sent as a coronation “present” to Henry by the Dauphin.

As described above, the Henry of the movie reacts to this “present” with self-deprecation, even excusing the insult.

The reaction of Henry in Shakespeare’s play Henry V could not be more different. He answers the Dauphin full of defiance and anger:

And tell the pleasant prince this mock of his

Hath turn’d his balls to gun-stones; and his soul

Shall stand sore charged for the wasteful vengeance

That shall fly with them: for many a thousand widows

Shall this his mock mock out of their dear husbands;

Mock mothers from their sons, mock castles down;

And some are yet ungotten and unborn

That shall have cause to curse the Dauphin’s scorn.

Finally, let’s take look at the already mentioned exchange between the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry again, and compare the movie’s version of this exchange with Shakespeare’s version from his play Henry V.

The Archbishop essentially says the same thing both in the movie and in Shakespeare’s play Henry V, stressing the rightfulness of the claim of the English to the French crown. He describes the Salic law, according to which women are excluded from the inheritance of the French throne. This law had been invoked by the French to exclude the English kings from inheriting the French crown (because the English claim rested on female lineage).

He then explains why this law should not apply for France – it only applies to the Salic (or Salique) land, which is outside of France. Therefore, this law can not be invoked to delegitimize the claim of the English to the French crown.

Henry’s reply to the Archbishop’s expositions in Shakespeare’s Henry V is exactly the opposite of how Henry reacts in the movie.

In Shakespeare’s play the Archbishop of Canterbury’s rousing words resonate in Henry. He becomes convinced of his claim to the French throne and is resolved to go to war to enforce this claim:

Archbishop …

Then doth it well appear that Salique law

Was not devised for the realm of France

…

the land Salique is in Germany,

between the floods of Sala and of Elbe

…

To hold in right and title of the female:

So do the kings of France unto this day;

Howbeit they would hold up this Salique law

To bar your highness claiming from the female,

And rather choose to hide them in a net

Than amply to imbar their crooked titles

Usurp’d from you and your progenitors.

King Henry V

May I with right and conscience make this claim?

Archbishop …

Gracious lord,

Stand for your own; unwind your bloody flag;

Look back into your mighty ancestors:

Go, my dread lord, to your great-grandsire’s tomb,

From whom you claim; invoke his warlike spirit,

…

Therefore, to France, my liege.

King Henry V …

Now are we well resolved; and, by God’s help,

And yours, the noble sinews of our power,

France being ours, we’ll bend it to our awe,

Or break it all to pieces …

In the movie, Henry contemptuously interrupts the the Archbishop. In contrast to Shakespeare’s Henry, he can’t follow the movie’s Archbishop’s much shorter explanations of the Salic law and rejects the idea that such an “old and impenetrable madrigal” should provide a reason for war against France:

Archbishop

It is said that the Salic law would have no succession if the French crown falls to a woman. Meaning, no rule left in the lineage of the female shall, by right, pass to her issue. Now, the law Salic, which is of Frankish land and tethered to said lands is not therefore legally bound and adherent at all, in fact, to the land of France, but to those of Francia, which, as you know, lies between the rivers of Elbe and Saale. I claim here, with proof that hence it follows that the law Salic, which has seen French sovereignty stolen as such from a true lineage …

King Henry V

I’m finding this story impossible to follow.

Archbishop

My liege, I question the so-called French king’s claim to the throne upon which he sits.

King Henry V

Is that so?

What confuses me now is why you are telling me this story.

Archbishop

My liege, I simply aim to bolster your claim to France should the need to meet her with force soon arise.

King Henry V

And you believe that need will indeed soon arise? … If we are to war with France, it will not come as a consequence of an old and impenetrable madrigal.

Given such distortions of Shakespearean themes, any reference to the movie as “based on Shakespeare’s plays” is completely unjustified.

Conclusion

What genre does The King belong to?

Is it maybe a historical drama, in the tradition of, for example, Waterloo? Historical dramas, while much of them is fiction, get the well-known historical facts mostly right. In contrast, The King distorts history to such an extent that it cannot be called a historical drama.

Given that it contains many Shakespearean elements, can it then maybe called a movie adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry trilogy, like, for example, the movie Henry V? The latter movie follows Shakespeare’s play quite closely. This is definitely not true for The King, and thus it cannot be seen as an adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays.

So is it then a historical fantasy movie, like the film 300? This genre doesn’t fit The King, either. It clearly wants us to take elements of its historical accuracy seriously. The makers of the movie made an obvious effort to make the costumes, the weapons and the armor historically accurate looking. Some of the battle scenes are also very realistic looking. It definitely wouldn’t want to be characterized as a fantasy movie, and we agree.

It seems that the best way to answer the question about The King‘s genre is to say that it is its own genre: a weird, bizarre mix of fact, fantasy, Shakespeare and politically correct moralizing.

Literature

Barker, J. (2007). Agincourt. The King, the Campaign, the Battle. London:Abacus.

Barker, J. (2009). Conquest. The English Kingdom of France in the Hundred Years War. London:Abacus.