Language in the “Grand Duchy of Finland” under Russian rule

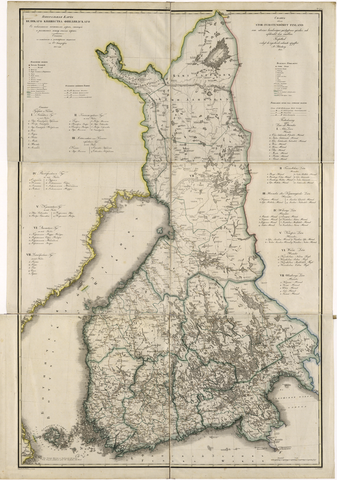

Beginning of the 19th century, during the “Finnish War” (1808-1809) between Sweden and Russia, Russia annexed Finland which became an autonomous “Grand Duchy” with the Russian Emperor as its ruler. Autonomy meant that Finland could maintain most of the laws and regulations from the Swedish times.

The usage of the Russian language was not enforced (except in the offices of the Governor-General) and not even promoted. The Finns could use the same languages they had used previously. Sermons for the Finnish speaking population in churches were in Finnish, but, though only about 15% of the population was Swedish speaking, Swedish had a prevalence everywhere else. It was used by the administration and in the courts, and, except in primary schools, the language used in all schools was Swedish.

In spite of the efforts of the Fennophiles (see Part 1) the Finnish language was regarded by many of the Swedish speaking elites as a primitive language, not suitable for sophisticated communication or literature.

Promoting the Finnish language and Finnish national identity

Soon after the Grand Duchy’s establishment, a new movement developed at the Academy of Turku: the “Turku romantics” (Turun romantiikka). This movement continued the tradition of the Fennophiles—H. G. Porthan had been a professor at the Academy until his death in 1804.

The movement was also influenced by the romantic nationalistic movements which spread in Europe—in particular in Germany—after the Napoleonic wars. The theoretical underpinning for these movements was supplied by philosophers like J. G. von Herder and G. W. F. Hegel. Von Herder, in particular, emphasized the role of folklore, culture and also language as important constituents of the spirit of a national group.

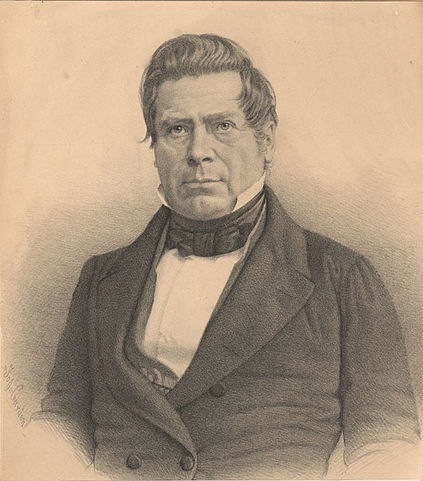

Adolf Ivar Arwidsson

Adolf Ivar Arwidsson was the most outspoken representative of the “Turku romantics” movement. He studied at the Academy of Turku until 1817 and became lecturer there in the same year. Soon he started publishing comments about Finnish society and politics.

Arwidsson thought that the Finnish language had an existential importance for the Finnish nation. He criticized the fact that large segments of Finnish society—the Finnish speakers—were at a disadvantage in society, for example at court, because the official language was Swedish that they didn’t understand. To promote Finnish, he demanded a professorship at the Academy for teaching Finnish. He sharply criticized many other developments in the new Grand Duchy, too.

Arwidsson worked in Finland only for five years; his political journal Åbo Morgonblad was prohibited by the Russian Emperor in 1821 because of its perceived radicalness, after only eight months—at the initiative of Finnish officials in Helsinki and in St. Petersburg. In 1822 he was banned from the University for life by the Emperor—again at the initiative of Finnish officials—and in 1823 he left Finland for Sweden.

In 1828, after a fire in Turku, the Academy was moved to Helsinki, the new capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. The Academy, under its new name “University of Helsinki”, remained a place where the connection between the Finnish language and Finnish national awakening was kept alive. In 1830 the Saturday Society (Lauantaiseura) was founded by some students and teachers. Johan Ludvig Runeberg, the later famous poet, was among the founding members and Johan Vilhelm Snellman joined the Society later.

Fennomania

In their own way, both Runeberg and Snellman played an important role later in the promotion of Finnish national consciousness. Snellman, in particular, became one of the leading figures in the new Fennoman movement.

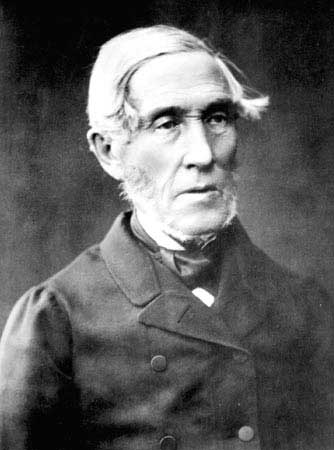

Johan Vilhelm Snellman

The way Snellman saw the language situation in Finland was this: Swedish was suppressing Finnish for the time being. However, Swedish will inevitably disappear sooner or later. If, by that time, the position of Finnish was not strong enough, Russian, which was waiting around the corner, will win and Finland will be russified.

Thus, in order to save Finnish national identity, it was an urgent task to support the Finnish language in every way possible. Of particular importance was that it becomes the language of the elites. Also, Finnish needed to develop into a literary language. These ideas found an expression in Saima, the Swedish-language journal Snellman started to publish in 1844. Like Arwidsson’s journal 25 years earlier, Saima was prohibited shortly after its start, in 1846, for similar reasons.

The Fennomans’ idea about Finland was “one nation, one language”, where “language” was equal to “Finnish”. They wanted to achieve that both the Swedish speaking rural population and the educated elites adopt Finnish as their language, at a time when most of those elites were still Swedish speaking. Towards the future status of Swedish Snellman had quite a harsh attitude: it “has no power of survival” and, in any case, “the future language of the small Swedish population proper is a matter of relative inconsequence”.

In parallel to the efforts of the Fennomans, there was progress in Finnish-language publication. The number of books published in Finnish expanded greatly. The optimism regarding the literary capabilities of the Finnish language, as expressed by the Fennomans, seemed justified, too: Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala—a collection of Finnish folk poetry from Karelia—became a literary sensation in 1835. From 1863 on Alexis Kivi started publishing his Finnish-language plays and poetry. In 1873 he wrote one of the first Finnish language novels, The seven brothers.

One interesting thing was that, just like in the earlier Fennophile movement (mentioned in Part 1) all members of the Fennoman movement, fervently promoting the Finnish language and Finnish culture, were Swedish-speaking intellectuals. Even Alexis Kivi had a Swedish name originally: Stenvall (the Finnish word kivi means stone in English, which means sten in Swedish).

Fennomania and the authorities

All high ranking Finnish officials belonged to the Swedish speaking elite. They were in general suspicious towards the propagation of the Finnish language because of its perceived potential for radicalism and simply because they preferred keeping the status quo with regard to language instead of instituting changes. It was Finnish officials who initiated the banning of the journals Åbo Morgonblad and Saima (though the language issue didn’t play a direct role in their banning).

The attitude of the Russian authorities—the Russian Governor-General, the State Secretary for Finland, residing in St. Petersburg, and the Emperor himself—to the language issue changed over time, depending on how they evaluated the potential danger for Russian rule.

It also depended on external circumstances. For example, Alexander Menshikov, Governor-General between 1831 and 1855, viewed the Fennoman movement with suspicion. Maybe because of the previous “troubles” with publications by Finnish nationalists like Arwidsson and Snellman and also because of the threat of nationalistic ideas coming from Europe in the wake of the 1848 uprisings, Menshikov issued a censorship decree in 1850 to limit Finnish language publications to those with religious or practical economical topics.

In contrast, the next Governor-General, Friedrich Wilhelm Rembert von Berg, in office between 1855 and 1861, apparently had quite a positive attitude towards Fennomania. Von Berg and Snellman even became friends which was probably helped by Snellman’s display of unflinching loyalty towards Russian rule. Under von Berg’s governorship Menshikov’s censorship decree was not enforced and it was repealed altogether in 1860.

Maybe because by the 1850’s and 1860’s it was clear that Fennomania didn’t pose a threat to Russian imperial rule, there was a constant stream of improvements in the status of the Finnish language.

In 1851 a decree was passed according to which judges working in Finnish language communities had to pass a Finnish language test. In 1858, the first Finnish-language secondary school was opened in the city of Jyväskylä.

Probably the greatest success for the Fennoman cause was when, after a meeting with Snellman, Emperor Alexander II issued the Language Edict (Kieliskripti) in 1863. This Edict decreed that, after a 20 year transitory period, the Finnish language will have official status in Finland.

Svecomania: defending the Swedish language against Fennomania

The Fennomans’ views and the successes they achieved were seen as a threat by many in the Swedish-speaking segment of the population. The response among Swedish speakers was the Svecoman movement, started by the student of philology, and later professor at the University of Helsinki, Axel Olof Freudenthal around 1860.

The Fennoman demand “one nation, one language” was rejected by the Svecomans who wanted to maintain their own culture and language—and, as far as possible, the existing privileges enjoyed by the Swedish language. Instead, the Svecomans’ slogan was: “two nations, two languages”. During the rest of the 19th century, the fight between Fennomans and Svecomans determined much of the political life in Finland.

The Finnish Diet is summonned

In addition to issuing the Language Edict mentioned before, Emperor Alexander II made another momentous decision in 1863: he summoned the Finnish Diet, a kind of traditional parliament, which had not met since 1809.

While in previous Diets the interest groups were defined by the four Estates—nobles, clergy, burghers and peasants—, in this new Diet there was a new kind of division, crossing through Estate boundaries: the two language movements Fennomans and Svecomans and for a number of years also an additional movement, the Liberals, who were quite neutral on the language issue.

The Liberals disappeared—often by joining the Svecomans—around the 1880’s. The Fennomans—which became the “Finnish Party”—had the majority in the Estates of the clergy and of the peasants, and the Svecomans—which became the “Swedish Party”—had the majority in the Estates of the nobles and the burghers.

Several language issues remained unsolved: although in 1884, after the 20 year transitory period, Alexander II’s Language Edict came fully into force, there were many problems with applying it in practice. Many controversies surrounded also the teaching language in secondary schools, though the Fennomans achieved a success on this issue: by 1889 the number of students in Finnish-language secondary schools reached the number in Swedish-language secondary schools .

Russification

Just like in Finland and other European countries, nationalism arose in Russia, too. It expressed itself in expanding Russian influence in all areas of the Russian Empire.

By 1890 the only autonomous area inside the Empire was Finland. To many Russians, Finland seemed with its autonomy and Western orientation an anomaly inside the Russian Empire. High ranking nationalistic minded Russian officials thus tried to influence the Emperor to curtail Finland’s autonomy. Nicolai Bobrikov, appointed to Governor-General in 1898, tried to undermine Finnish autonomy in many ways, one of which was establishing Russian as the administrative language for Finland.

Bobrikov wrote: “Not a single nationality belonging to the Russian Empire has the right not to use Russian, the Imperial language, in any area of government life … There is no reason to allow Finland exemption from this general rule.”

The Language Manifesto, signed by the Russian Emperor Nicholas II in 1900, made Bobrikov’s ideas a reality: Russian must become the language of higher administration in Finland. For the future, Bobrikov foresaw that Swedish would be totally abandoned as official language, with only Russian and Finnish remaining.

Bobrikov was the main motor behind these developments, and it seems that his assassination in 1904 slowed down russification. Though the Language Manifesto was never repealed until the end of Russian rule in 1917 and other attempts at russification followed, the radical plans of Bobrikov were never realized and Finland was never fully russified.

The dynamics of the language issue

As it is shown above, the development of the language issue and the emergence of a Finnish national identity during the 19th and early 20th century was a very complex process. In contrast to the separationist movements of the 18th century, language issues played an important role.

A number of players were involved: the Finnish speaking population, the Swedish speaking population and the Russian authorities. Part of the Swedish speaking intelligentsia was fervently supporting the cause of the Finnish language and Finnish culture. All of them had different interests.

What they saw as important changed over time. The attitudes of the Russians changed to both the Finnish and the Swedish language several times. Inside the Swedish speaking intelligentsia there was a counter-reaction to the Fennoman tendencies of some of its members, and a counter-movement—the Svecomans—emerged.

All this took part with European cultural and political trends as a background—revolts in other parts of the Russian Empire against Russian rule, e.g. in 1831 in Poland, revolutions in 1848, nationalistic trends. These also influenced the dynamics of the language issues inside Finland.

Most of the important persons influencing the events were either Swedish speaking intellectuals or Russian administrators. Finnish speakers didn’t seem to play much of a role during much of the 19th century. This can be explained by the fact that it took a long time for a Finnish speaking intelligentsia to develop. As mentioned above, the first Finnish language secondary school was opened as late as in 1858.

Also, somewhat curiously, there didn’t seem to be any movement in the Swedish speaking population to re-unite Finland with Sweden—though Finland had been part of Sweden for 650 years previously and though the Fennoman movement were a real threat for Swedish speakers. The Swedish Kingdom didn’t show any such intentions, either.

The role of Russian rule in the emergence of Finnish national identity

For Finland, Russian rule meant more independence than in most periods of its history: it became an autonomous Grand Duchy, with its own laws, own Parliament (the “Diet”, which, admittedly, didn’t sit between 1809 and 1863), own army which wasn’t to be deployed in other parts of the Russian Empire, own currency, even its own postal service.

This was in contrast to Swedish rule which, during the course of the 18th century, merged Finland more and more into Sweden. Finnish laws were the same as Swedish laws, there was no separate Finnish Diet (all Finnish deputies sat in the Swedish Diet in Stockholm).

The Grand Duchy was not a democracy by any means: the Grand Duke—the Russian Emperor—had all executive powers. Strict censorship controlled publications. The Diet, the only important elected institution, was to meet only when summoned by the Emperor. Also, in late 19th century, Finnish autonomy appeared more and more as an anomaly for Russian nationalists who wanted to restrict it.

Still, autonomy gave the population of Finland the opportunity to start sorting out among themselves national identity issues, like education and the language issue, relatively undisturbed—in particular after the Finnish Diet started to sit again in 1863.

Would all this have been possible under Swedish rule? Maybe. Swedish rule was definitely more liberal than Russian rule. But Finland under Swedish rule had only little autonomy. It probably would have had to acquire an autonomy first, comparable to what the Grand Duchy under Russia enjoyed, and then continue with sorting out language and national identity issues.

Independence

Finland declared its independence from Russia on 6 December 1917 and in 1919 a constitution was adopted which stated that Finland had two national languages: Finnish and Swedish.

There were still fights to be fought in the future related to language issues—for example regarding the status of the Åland Islands, where a Swedish speaking population lived. However, none of these fights were comparable in importance to the existential fights which Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns fought against each other and against Russia in order to promote and defend their languages and their identity.

Be the first to comment on "Language and Nation: Finland, Part 2. Russian rule"