Longing for The Great Replacement

Part 2 of this series was about criticisms of the Great Replacement idea by people who tried to downplay the extent of the demographic changes happening in Europe.

Another group of people accepts the demographic reality of the “Great Replacement”. However, they welcome these changes as a means to increase the “diversity” of European societies.

Consider the following two citations from leftist German politicians.

The first of these is from the German Green Party politician Stefanie von Berg. She said this in 2015 at the Parliament of the city-state Hamburg:

Madam President, ladies and gentlemen, our society is about to change, our city is going to change radically, and I believe that in 20-30 years we will have no more ethnic majorities in our city. And that’s what migration researchers say: we’ll live in a city where – simply said – our city lives on, we have many different ethnicities – many people – that we have a super-cultural society. That is what we will have in the future. And I’ll tell you quite clearly, especially in the direction of the Right: that’s a good thing!

The second citation is also from a German Green Party politician, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, a leader of the German Green Party. She had this to say at the Congress of the Green Party in November 2015:

We talk about how our country will look like in 20 to 30 years. It will be younger. How great is this? We have been talking about demography for so long. It will become more diverse. How great is that? We have been looking forward to this for so long … Our country will change, and drastically. And I’m looking forward to it!

Göring-Eckardt was referring to the expected changes caused by the mass migration wave of mid-2015.

Both politicians acknowledge the demographic reality of the “Great Replacement”, the “radical” and “drastic” changes happening in German society as a result of mass immigration. Von Berg expects that a German majority in Hamburg will disappear within a couple of decades, to be replaced by a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society. She is looking forward to these changes, just as Göring-Eckardt does.

How will this new society, imagined by these leftist politicians – and by many others – look like?

It will be a kind of Utopia: ethnically and culturally “diverse” and “colorful” (bunt in German), vibrant and peaceful. Tolerance of cultural practices of the different groups will rule. There will be no Leitkultur – the “leading culture”, that is the original German culture which is supposed to be the culture new migrants integrate into. A mixture of many ethnicities and cultures will replace it, making the idea of a “German people” and of a “German nation” obsolete. One can find the same kind of ideas in many Western European countries, pushed by politicians, the media and academia.

To achieve this replacement of European societies with multicultural, multi-ethnic societies it helps if the European natives can be convinced that their own culture is not better than the cultures of the immigrants – and that it is in fact worse. Or maybe, that they don’t have a culture worth mentioning at all.

Rejecting European culture

Denying the existence of the nation’s culture

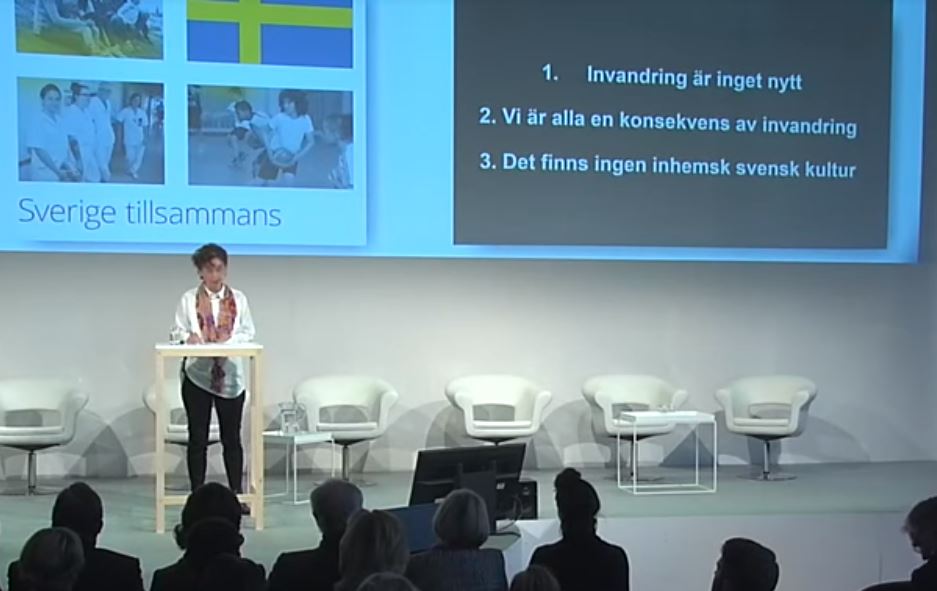

Sverige Tillsammans (Sweden Together) is a program initiated by Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, with the aim of creating better conditions for immigrants in Sweden. The picture below shows Ingrid Lomfors, a Swedish historian, talking at a conference of Sverige Tillsammans in 2015. Note the third point on the screen behind her, saying: Det finns ingen inhemsk svensk kultur, in English: There is no native Swedish culture.

Lomfors is a prominent historian. In 2005 she was appointed as director of the Gothenburg City Museum, and in 2014 she became the Head of the Living History Forum in Sweden.

In Germany, Aydan Özoğuz, a Social Democratic politician, became a member of the Federal Government, as Federal Commissioner for Immigration, Refugees and Integration in 2013. In May 2017 she wrote an article for the German newspaper Tagesspiegel, in which she attacked the idea of a Leitkultur – the leading culture of Germany, in other words, the German culture, about which she had this to say:

A specifically German culture, beyond language, is simply unidentifiable.

Her article led to hot debates in Germany, and many people were angered by her statement about the non-existence of a German culture, but she kept her position until the next Federal elections, in 2018.

Contempt towards the nation’s culture

Part of the enthusiasm for multiculturalism might be explained by a contempt or low regard for the culture of one’s own country.

Sweden, again, is the country which provides some of the best examples for these kinds of attitudes among the elite. For example Swedish Ex-Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt, a conservative politician, said this:

Only barbarism is genuinely Swedish. All further development has come from abroad.

It’s no surprise if someone with an opinion like this about the culture of his own people welcomes its replacement by less “barbaric” cultures.

One other sign of disregard for the own culture could be the recent appointment of Qaisar Mahmood to the Swedish National Heritage Board as Head of Department. He was born in Pakistan and moved to Sweden at the age of seven. He describes his qualifications for his new job in an interview like this:

I have studied political science and economics. I have a socioeconomic degree. I have not read any points of archaeology at university or anything about cultural heritage.

His main qualification, in fact, seems to have been his strong stand on “diversity” and a suspicious attitude towards people “who say they want to safeguard the cultural heritage”. He wrote this on the web site of Swedish Radio:

Just sit in front of your computer and google “cultural heritage”.

You will get pictures of rune stones, medieval churches, folk costumes and hometowns.

You will also find articles written by people who say they want to safeguard the cultural heritage, but if you dig a little deeper into the arguments you can find resistance to change – a kind of cultural heritage washing, where cultural heritage is used as a blanket to hide cloudy motives.

Hating one’s own nation

Others, on the more extreme Left, go further: they openly hate their own country and its population. One can observe this again and again during demonstrations of far-Left activists in Germany. For them, it is not enough that Germans become a minority in Germany. They apparently can’t wait to see Germans completely disappear as a people.

The poster shown below, held up by leftist demonstrators in Germany, says: “Germany you rotten piece of shit”.

To understand the picture below one has to realize that during World War II the British Royal Air Force (RAF) fought an area bombing campaign against Germany, aimed at living quarters of big German cities. The aim was to demoralize the German population. This didn’t happen, but a number of cities like Hamburg, Berlin and Dresden were almost completely destroyed, resulting in large numbers of civilian deaths. During the closing weeks of the war Dresden – hosting at the time many German refugees fleeing from the Russians – was bombed. A fire storm arose and up to 25,000 people died.

The architect of this bombing campaign was Marshal of the RAF Arthur “Bomber” Harris. The picture below shows a demonstration of the feminist movement FEMEN in Dresden on 13 February, 2014, the anniversary of the bombing attack on the city.

The woman on the left, thanking “Bomber” Harris, is Anne Helm, who at the time of the demonstration was member of the Pirate Party and had been member of a Berlin borough assembly for that party since 2011. After initially denying that she was the masked woman thanking “Bomber” Harris, she admitted it and and called it a “dumb action”. The incident didn’t affect her chances in German politics: she joined The Left Party in 2016, and now she sits in the Berlin Parliament for that party.

The reality of “diversity”

Many of the “radical” and “drastic” changes in European society foreseen by von Berg and Göring-Eckardt are already happening as the result of mass immigration. What is the chance that these changes will result in the peaceful, positive, multi-ethnic, multi-cultural future envisioned by these people?

There has been quite a lot of research about the effects of diversity – ethnic and cultural – on society. We show here the results of a few studies.

Diversity and trust

One area of this kind of research investigates the effect of diversity on trust between members of the community, altruism and community cohesion.

Two types of trust are considered in this type of research: generalized (or societal) trust and inter-group trust. The first one is trust, in general, to any member of the society. An example for the second one is inter-racial trust, like trust of a black person towards a white person.

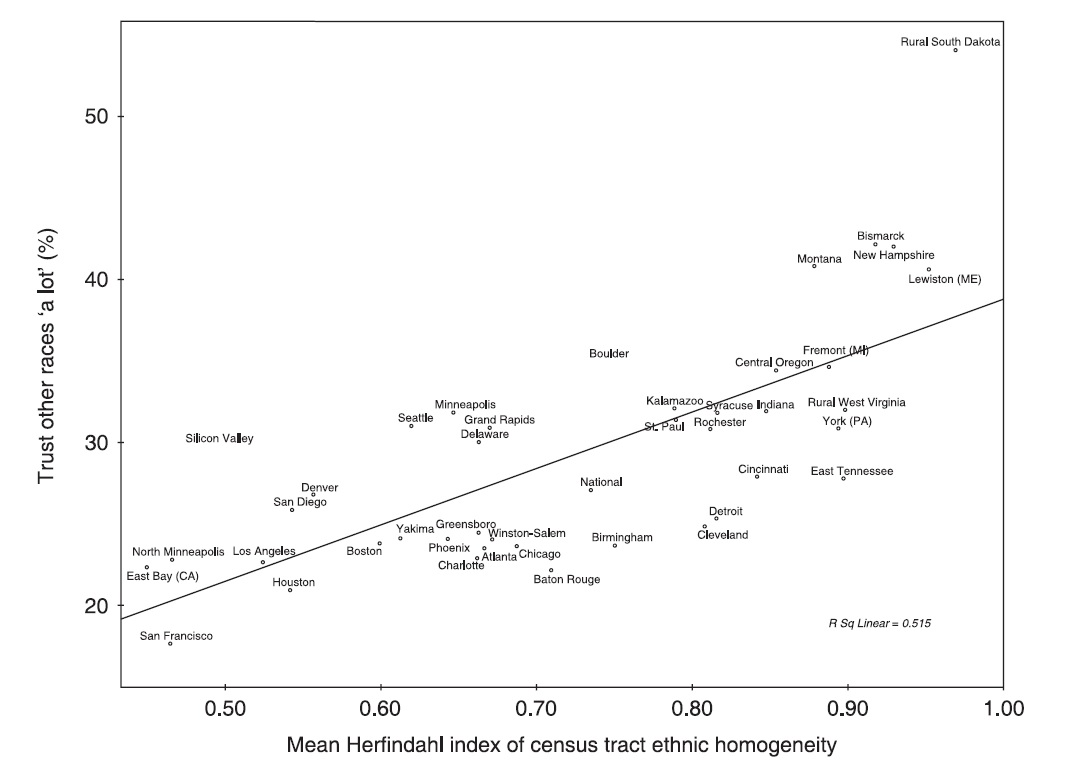

In 2001, political scientist Robert D. Putnam researched trust inside 41 US communities (sample size: 30,000 subjects). The communities differed greatly with regard to ethnic diversity,

ranging from large metropolitan areas like Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston and Boston to small towns and rural areas like Yakima, Washington, rural South Dakota and the Kanawha Valley in the mountains of West Virginia …

Los Angeles and San Francisco (roughly 30–40 percent white) are among the most ethnically diverse human habitations in history, whereas in our rural South Dakota county (95 percent white) celebrating ‘diversity’ means inviting a few Norwegians to the annual Swedish picnic.

(Putnam, 2007, p. 144)

The figure below shows how trust to other ethnicities differs as a function of ethnic homogeneity: the larger the homogeneity, the higher the trust among members of the communities. Formulated differently, the larger the “diversity”, the lower the trust towards members of a different ethnicity.

Thus, contrary to the multicultural slogan “diversity is our strength”, people living in “diverse” communities experience less community cohesion and trust towards other members of the community who belong to a different ethnicity: diversity decreases inter-group trust.

In addition, trust in more “diverse” communities decreases also towards the own ethnic group (Putnam, 2007, p. 149). Thus, it seems that more “diversity” leads to a lower generalized trust felt towards the rest of society, too.

Putnam – a supporter of social “diversity” – was apparently disturbed by the results of his research. Though he published his methodology and his data on a web archive of the University of Connecticut, he didn’t publish a full paper describing the results until 2007.

In a similar project, but in the European context, Hooghe et al. (2010) did a country level analysis of the effect of diversity on generalized trust. They used a large number of indicators of immigration for 20 European countries, gathered from an OECD survey from 2002. Some of these indicators were: ‘Number of foreigners in 2002’, ‘inflow of foreigners in 2002’, and ‘percentage of the inflow of foreigners in 2002 from Islamic countries’. Generalized trust for each of the countries was determined based on the European Social Survey from 2002-2003.

In contrast to Putnam’s results, the results of Hooghe et al. (2010) provided only relatively weak support for the idea that diversity decreases generalized trust. Only few of the correlations between diversity indicators and trust were statistically significant. The authors of the article conclude:

The implication of our study certainly does not mean that ethnic diversity would or could not create social tensions or social problems. But our analysis has revealed that diversity does not exert the consistent and strong negative effects often attributed to it.

Still, the authors acknowledge that there was a tendency for a negative effect of diversity. They write:

However, we do acknowledge a negative although weak and inconsistent tendency in the relationship between diversity and generalized trust in Europe as well.

In fact, for the arguably most important diversity indicator – percentage of foreigners in the country – there was a statistically significant negative relationship between diversity and generalized trust (but only after Switzerland, an outlier, was removed from the analysis).

Several things are worth mentioning: first, the data for the research was from 2002 and 2003, thus relatively old. In particular, it doesn’t contain the large increase in the foreigner population in Europe in recent years, in particular since 2015.

Second, in 2002 the immigrant proportion of the population was less than 10% in each of the 20 countries, except for Switzerland. In other words, more than 90% in most of the countries was non-immigrant. Thus, the diversity variation between the countries was far smaller than the diversity variation between the communities in Putnam’s research.

Third, immigrants in Europe tend to concentrate in big cities, thus much of a country’s population – those living outside big cities – might not have much to do with foreigners.

Fourth, the study takes only foreigners into consideration but not people born in the country but having a foreign background. For example, currently more than 20% of Germany’s population has a foreign background, while the immigrant population is 14.8%.

Another study looking at diversity and its effect on trust in the European context is from Dinesen & Sønderskov (2015). Similarly to Putnam (2007) – and in contrast to Hooghe et al. (2010) – they focused on the community level. In fact, the study looked at ethnic diversity in residential “micro-context” in Denmark, meaning ethnic diversity in the vicinity (within 80 m, i.e. 87 yards) of the homes of the study’s subjects. The idea was that the level of ethnic diversity so near around where a person lives is a better indicator of actual exposure to foreigners than the more rough, country-level measures of diversity used, e.g., by Hooghe et al. (2010).

Dinesen & Sønderskov (2015) used data from the Danish national population register to determine ethnic diversity and data from the European Social Survey (ESS) to get generalized trust values for every subject.

They found a moderate but statistically highly significant effect of diversity on trust. They write:

[There is] strong evidence that ethnic diversity in the micro-context has an independent negative impact on social trust …

And they add:

we find no evidence that the impact of ethnic diversity varies by either neighborhood income or inequality

Instead of looking at the effect of ethnic diversity, Klasing & Beugelsdijk (2014) investigated the effect of cultural diversity on generalized trust in 98 countries and in 152 regions inside 44 European countries.

To determine cultural diversity, they used data from the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS). Altogether, responses from approximately 350,000 individuals were used.

To determine generalized trust, they used answers to the question Generally speaking do you think that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful? in the WVS/EVS results.

They then correlated the cultural diversity values with the generalized trust values for each of the countries and regions. For the country level analyses (but not for the regional analyses) hey also calculated the effect of the diversity of a number of other factors – e.g. language diversity, religious diversity and genetic diversity – on generalized trust. They found that two variables had the most important negative effect on trust: diversity of political values (an aspect of cultural diversity) and genetic diversity, whereby the first one was more important than the second one. The conclusion of the authors:

We find that societies characterized by high levels of cultural diversity—especially with regard to political values—have lower levels of trust and that cultural diversity is the most important predictor of trust.

When looking at its relevance for the European immigration issues, this research has the same problems as Hooghe et al. (2010): its country-level analysis, and even its regional level analysis are probably too rough.

Summary of “Diversity and trust”

There are many consequences of diversity on society. There is no doubt that some of these are beneficial. For example, Stahl et al. (2010) found that diversity increases creativity in work groups (though it leads to “task conflict and decreased social integration”). Research also shows a positive effect of cultural diversity on GDP growth – though other studies indicate that ethnic diversity is associated with weaker economic performance and that it increases conflict in societies (Bleaney & Dimico, 2016).

This section focused on trust, an important correlate of social cohesion.

As shown above, some studies found a strong negative effect of diversity on both generalized trust and inter-group trust (Putnam 2007). In some other studies – e.g. in Hooghe et al. (2010) – the negative effect of diversity turned out to be weaker. One study – Klasing & Beugelsdijk (2014) – found that the negative effect of cultural diversity on generalized trust was stronger than that of genetic diversity. Some other studies even found a positive effect of diversity on trust.

However, the current general consensus among researchers about the effect of diversity – ethnic and / or cultural – on generalized trust seems to be that this decreases generalized trust.

Thus, the empirical evidence casts – at the very least – strong doubts on the multi-ethnic, multi-cultural visions of leftist activists. Diversity, instead of being a strength, weakens social cohesion in many cases.

Note that only one of the studies cited above – Putnam (2007) – investigated inter-group trust, in addition to generalized trust. But inter-group trust is particularly relevant in the European situation, with growing problems with ghettoized immigrant populations, and continuing mass immigration. Inter-group trust will have a large affect on how the native population reacts to immigrants, and vice versa. Only Putnam (2007) provides some insight into this aspect of the affect of diversity on trust. However, Putnam (2007) looked only on ethnic diversity, and not cultural diversity. In the European context, it would be important to look at the affect of cultural diversity on inter-group trust – for example, trust between native Europeans and Muslim immigrants.

Identity loss

An additional effect of diversity is inevitable: a loss of cultural identity.

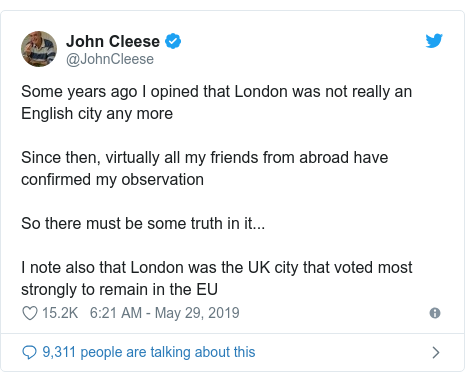

A recent Tweet by English comedian John Cleese – of The Life of Brian and Fawlty Towers fame – expresses this sentiment:

Loss of cultural identity has long been recognized as a problem and even as a mental health hazard. For example, an article in the journal World Psychiatry writes this:

The loss of one’s social structure and culture can cause a grief reaction … if the symptoms cause significant distress or impairment and last for a specified period of time, psychiatric intervention may be warranted.

Such problems are acknowledged and are treated with understanding and sympathy when they affect non-European migrants who arrive in a new cultural environment, for example here and here, or indigenous non-European people living in a Western country, for example Indians in Canada.

In contrast, complaints about the loss of identity for indigenous European populations, as a result of the continued growth of immigrant populations among their midst, have typically been met with ridicule and scathing criticism. People who voice such concerns are routinely labeled as “xenophobe”, “far-right”, “racist” and “Nazi”.

One example is the reaction to John Cleese’s Tweet. It was ridiculed and called “racist” by many famous and less famous people. The following is a headline from The Sun newspaper:

The BaM (Becoming a Minority) project

In Amsterdam, only one third of the youth under the age of 15 is now of native Dutch origin. The article with the title Ethnic Dutch a minority in big cities, so how do they integrate?, reporting about this in the online journal DutchNews.nl describes the research project Becoming a Minority (BAM), conducted by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The project is based on the observation that native Europeans are now the minority – or are close to becoming the minority – in a number of big cities in Europe. The project’s leaders expect that this will be more common in the future and their intention is to find out

[h]ow do people engage with each other in these neighborhoods? Do they experience conflicts and, if so, what are these about? … With the BaM project we hope to contribute to the understanding of what makes cities good places to live in. To study under which conditions people interact with each other in a way they find satisfying, and, on the other hand, when conflicts are more likely to arise and what can be done about that.

From an article in DutchNews.nl.

The cities the project will investigate will be these: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Malmö, Hamburg and Vienna.

The project’s web site indicates that replacement of Europeans as the majority population is accepted as a fact, without any discussion. The aim of the project is simply to research the consequences of this fact and give advice to politicians about solutions to the resulting problems.

What do the people think?

How do people in Europe react to the prospect of becoming a minority in their own countries and to losing part of their national identity?

The above article about the BaM project has the comment section disabled, with the justification:

Unfortunately we have had to suspend comments on this article due to the volume of replies which break our guidelines.

It seems that too many people wrote angry comments under the article, upset by the idea that now the Dutch should change their identity, in their own cities, in order to integrate into the new multicultural Netherlands.

Many Europeans, of course, don’t mind becoming a minority – and, as we have seen, they often long for this to happen. Others do not care much: they might be too preoccupied with their day-to-day problems.

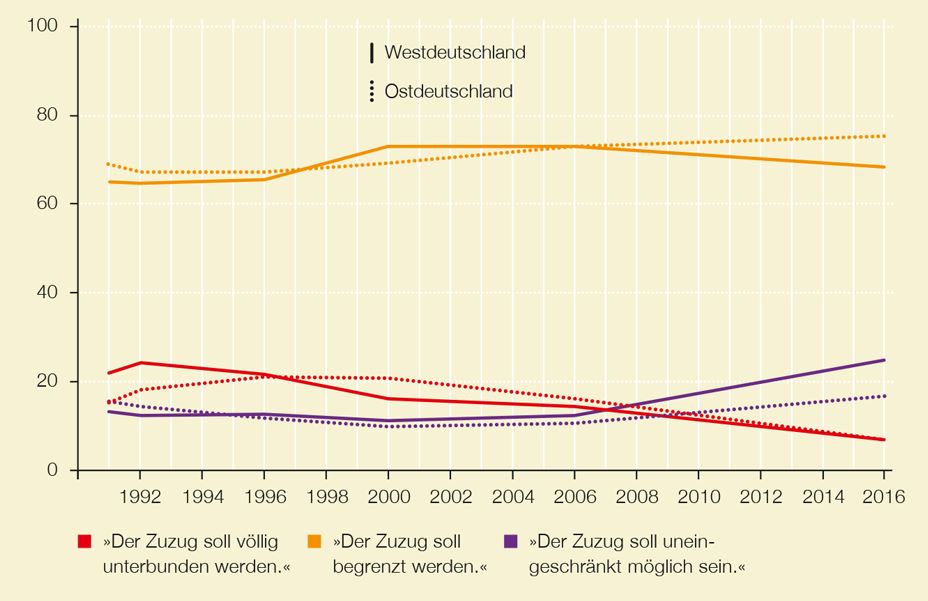

But many others don’t agree with the multi-ethnic, multi-cultural vision prescribed by leftist politicians for their future. The following chart shows the results of a recent poll in Germany, about the attitudes of Germans concerning the intake of more asylum seekers.

The dashed lines show the results for East Germany, the non-dashed lines for West Germany.

Red indicates a full stop for the intake of asylum seekers, yellow indicates that intake should be limited, and purple indicates that intake should be unlimited.

The chart shows that a large majority is for limiting the intake of asylum seekers in Germany. Note though that the percentage of Germans who are for an unlimited intake of asylum seekers has been continuously growing since around 2006. In 2016 their percentage in West Germany reached about 25% of the population.

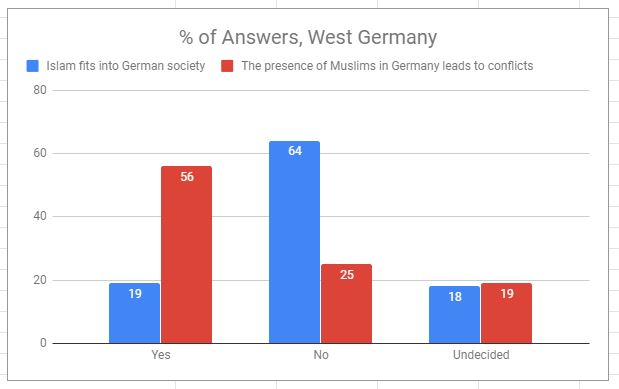

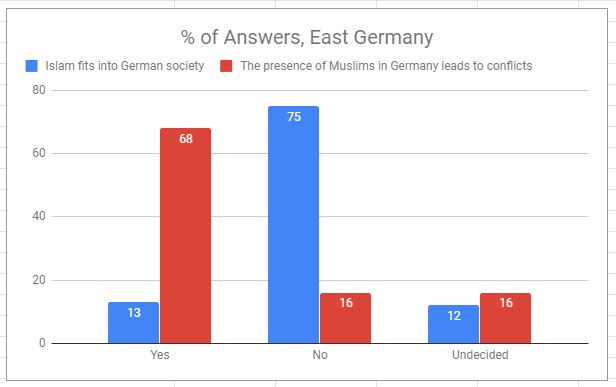

The same poll also asked about attitudes concerning Islam in German society. The following two charts show some of the results.

As shown above, a large majority, both in West and East Germany, think that Islam does not fit into German society. Also, a large majority, in both parts of Germany, expects conflicts resulting from the presence of Muslims in Germany.

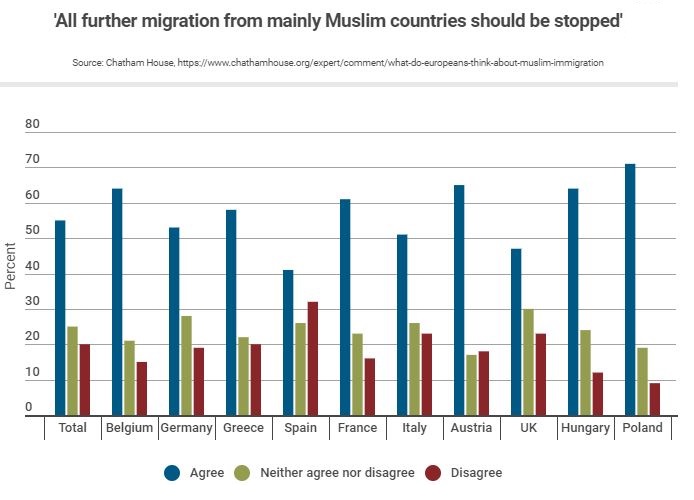

In the United Kingdom, in 2017 Chatham House conducted a poll of 10,000 people from ten European countries about their attitudes to further Muslim immigration. The article describing the poll’s results on Chatham House’s web site calls them “striking and sobering”.

On average, 55% agreed that all further Muslim immigration should be stopped. 20% disagreed, and 25% were undecided. The chart below shows the results for the ten countries.

Summary and conclusions

This Part of the series discussed the views of politicians and others who accept that large demographic changes are happening in Europe, resulting in native Europeans becoming minorities in their own countries, but who welcome these changes.

Research evidence shows that the multi-ethnic, multicultural societies these politicians – with the help of much of the media and academia – are in the process of creating will be very problematic. Though they might have some positive features, like higher creativity in work groups, they will be plagued by problems such as low societal trust and a higher incidence of violent conflicts and confrontations.

The poll results described above show that, at least in Western Europe, there is a wide rift between the opinions of the people and of their politicians. With few exceptions, most leading main stream politicians in Western Europe and in the European Union follow German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open border policies regarding immigration. In any case, nothing substantial is done to limit the stream of people arriving from Africa, the Middle East and Asia. And the majorities for limiting Muslim immigration in the Chatham House poll exist despite Europeans constantly being told by the media and by politicians things like “Islam belongs to Germany” (German Chancellor Angela Merkel) and despite they being continuously warned about the dangers of “Islamophobia”.

So, why do Europeans continue voting politicians into power with whose views they disagree so much on such important issues? Nobody really knows, but it is quite obvious that, after all, they do not see these issue as being so important, at least not in comparison to other issues affecting their lives. In fact, as the graph showing the attitudes of Germans about taking in more asylum seekers demonstrate, the percentage of those who do not want to put a limit on their numbers has been growing since about 2006.

And so, maybe, the visions of von Berg and Göring-Eckardt will turn into reality and in several European countries the native population will become one of several minorities within a few decades. As the research about the effect of diversity on societal trust and conflict shows, there is reason to assume that they will not enjoy their minority status.

Then again, though in recent elections in Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany the same mass-migration-supporting people were elected into power again, their parties lost votes. At the German Federal elections in September 2017, Chancellor Merkel’s party, the CDU, received the lowest number of votes since 1949. The established parties faced serious competition from parties on the right, like the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, or the Sweden Democrats – all of which are against mass migration and for limiting immigration to manageable levels.

Literature

Bleaney, M. & Dimico, A. (2016). Ethnic diversity and conflict. Journal of Institutional Economics (2017), 13: 2, 357–378.

Dinesen, P.T. & Sønderskov, K.M. (2015). Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: Evidence from the Micro-Context. American Sociological Review 2015, Vol. 80(3) 550–573.

Hooghe, M., Reeskens, T., Stolle, D. & Trappers, A. (2009). Ethnic Diversity and Generalized Trust in Europe : A Cross-National Multilevel Study. Comparative Political Studies 2009 42: 198.

Klasing, M.J. & Beugelsdijk, S. (2014). Cultural diversity and its Role for Trust Formation. CESifo Conference on Social Economics, Munich, 2014.

Putnam, R.D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Journal compilation © 2007 Nordic Political Science Association.

Stahl, G.K., Maznevski, M.L., Voigt, A. & Jonsen, K. (2010). Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies (2010) 41, 690–709.

To be continued.

Be the first to comment on "The Great Replacement: Myth, conspiracy theory, or reality? Part 3: “Diversity is our strength!”"