What they bring us is more valuable than gold.

This sentence was uttered in mid-2016 by Martin Schulz about the refugees streaming into Germany during 2015 and 2016. Schulz is a German Social Democratic politician and he was President of the Parliament of the European Union at that time. It was less than one year after the huge mass migration wave of 2015.

As we have seen in Part 3, Herr Schulz is not the only one to acknowledge the demographic fact of the “Great Replacement”, the wave of mass migration, but at the same time to insist that this is a positive thing.

So what is it that they bring to us that is more valuable than gold, according to Schulz? He continued by saying:

It is the unwavering belief in the dream of Europe. A dream that has been lost to us at some point.

Not a very tangible benefit, one could say. One could also ask: “How does he know what their dreams are?” In other words, typical politician-speak, in substance not to be taken seriously – except for the fact that it comes from a politician who was at that time a top-ranking EU official.

But others were more concrete in asserting the coming benefits of mass immigration. These are some of its asserted benefits:

- They are highly qualified people, doctors, skilled workers, etc., and as such, very valuable for the country where they arrive

- Whether highly qualified or not, they will be good for the economy

- They will pay our pensions. This will be necessary because of the sinking birth rate in every European country.

Even for such people it is difficult to deny that there are some negative consequences of mass migration, for example increased crime. Thus, when news appear about refugees committing crimes, it is asserted that

- These are “individual cases”, one should not “generalize”, this is nothing typical of the refugees, Europeans commit lots of crimes, too, etc.

- The perpetrator was under stress, “has gone through a lot”, lots of traumatic experiences, etc.

- Many of the crimes are actually misunderstandings: the criminal can’t help it, based on his culture he must commit some types of crime.

- The real problem is lack of opportunities for the criminal refugee – and it is the Europeans who are really responsible: they didn’t provide enough opportunities for successful integration into society

In the following few Parts of this series, we’ll examine these claims one after the other.

In this Part of the article series we’ll look at the educational level of the migrants of the current mass migration wave. We’ll also examine long term expectations in this regard. We’ll focus on German data because Germany has been the main target of this wave, in particular during 2015 and 2016.

The “Syrian doctors”: truth or legend?

In Germany, during the first, euphoric phase of the “welcome culture” (Willkommenskultur) in 2015 a legend was born about the high proportion of highly qualified refugees, in particular of “doctors from Syria”. This is what the newspaper Die Welt wrote in December 2015:

A statistic from the UN Refugee Agency shows that … 86 percent of Syrian refugees have a high school or university degree. The largest groups were students and professionals, including teachers, lawyers, doctors, bakers, designers, hairdressers and IT professionals.

This high number of professionals and skilled workers made the Die Welt author actually worried: Syria was seemingly losing its intellectual elite.

The legend of the “Syrian doctors” received support also in this article of the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from 2016:

Nearly 500 of the foreign doctors who were, after language and professional examination, newly licensed, came from the civil war country Syria. That was more than from any other country. With a total of more than 2,000 doctors, they are now the fourth largest group of foreign physicians.

This sounds impressive indeed. But, of course, this is a small number in comparison to the total number of refugees from Syria:

Since 2014, Syrians have been the largest group of those seeking protection in Germany. In total, around 770,000 have fled to Germany since the beginning of the civil war in 2011 (as of December 2018).

Even if we assume that more doctors from Syria came as refugees since 2016, when the article of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung was written – and assume, say, 3000 doctors in 2018 – it is still only 0.4 % of all Syrian refugees.

Thus, though the legend that a large proportion of Syrian refugees were doctors has a kernel of truth, it is mostly a legend indeed.

Education level and occupational qualification of the refugees

The article from Die Welt, quoted above, indicated that at least the Syrian refugees were very well educated. How correct are these claims? And a related question: what educational level and occupational qualifications do the refugees have in general?

There have been several attempts since 2015 to estimate the level of education of the refugees arriving in Germany. The results are often contradictory.

The German Federal Agency for Work (BA) found in 2017 that 30% of the migrants who were looking for work at the employment agency had very little school education or none at all.

The German Federal Institute for Vocational Training (BiBB) looked at the results of the above study by the BA again, and found that 25% of the migrants looking for work didn’t give any information on their level of education. BiBB made the assumption that they probably gave no information because they didn’t finish a school at any level. Based on this reasoning, BiBB concluded that 59% of the refugees had no finished education.

This conclusion by BiBB was heavily attacked. It was accused, by Herbert Brücker from the Nuremberg Institute for Labor Market and Employment Research, of creating a “science scandal” and, as a result, BiBB apologized and withdrew the results of its investigation from the Internet:

The Federal Institute for Vocational Training has now admitted that the text at least “gave rise to misunderstandings”. “Due to the significantly changed data and information situation, we have now removed the article from the Internet,” said a spokesman.

Neither the detailed data of the BM study nor those of the BiBB study seem to be available. However, the results of a later study, also from 2017, with Herbert Brücker from the Nuremberg Institute for Labor Market and Employment Research as one of the co-authors have been uploaded onto the Internet, thus we’ll describe its results here in some detail.

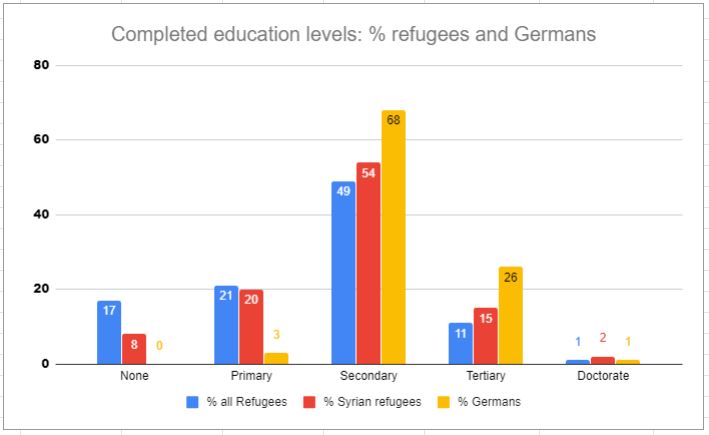

This study was a survey: it relied on interviews with about 4500 refugees. It turns out that it was also not without controversy: apparently 200 of the interviews were done “unprofessionally”, so that the results had to be re-calculated and a new version of the report was published in 2018. The following chart shows the results from that report (p. 28): the percentages of all refugees interviewed with a completed level of education, with the Syrians shown separately. The average German percentages are shown as well.

The chart shows that 38% of all refugees and 28% of Syrians had either no education at all or only primary school level education. This number was 3% in Germany.

61% of all refugees and 71% of Syrians had either a secondary or tertiary level education, including doctorates (PhD, medical, etc.). In comparison, 95% of Germans achieved the same levels of education.

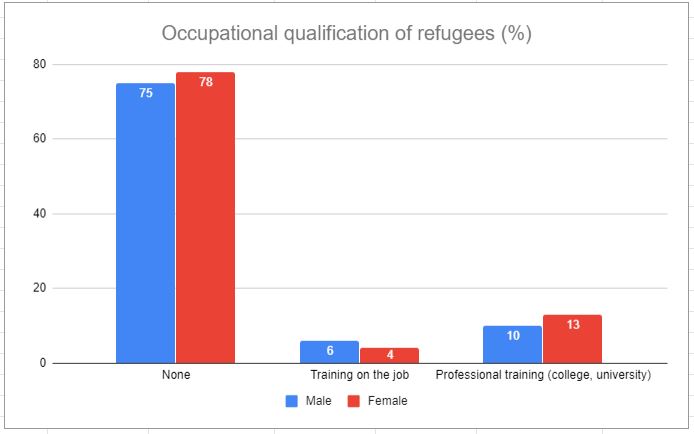

The survey also asked about the occupational qualifications of the refugees. The chart below shows the results (p. 22 of the Report).

Thus, according to the report, on average 76 % had no occupational qualification at all. Among those who did have a qualification, professionals trained at a college or university were in the majority. Females were both slightly more probable to have no qualification at all and to have professional training than males.

Thus, the idea that all refugees are analphabets is not true. But the opposite idea that they are all highly qualified people is obviously not true either. Almost 40% of them have very little education or none at all and close to 80% have no occupational qualification. But the rest have secondary or tertiary level education, though their percentages at those levels are a lot less than those of the German population.

What is also clear is that the initial, enthusiastic reports, for example by the UN Refugee Agency about the 86% Syrians who were supposedly mostly students, professionals or skilled workers, were unrealistic.

Currently, this survey still seems to provide the best available insight into the educational levels of refugees arriving in Germany, but one must keep in mind: the refugees were apparently not required to provide any documents in support of their claims about their educational level and occupational qualifications. Respondents in surveys like this do lie sometimes. One reason they lie is that they want to appear better, and thus there is some reason to assume that the real education level and the occupational qualifications of the refugees are possibly lower than the results of the survey indicate.

Vocational training in Germany

Initially, many big companies were very enthusiastic about the influx of a new potential work force as a result of mass migration, maybe partially because of the media reports (like the one above) about the high qualifications of the refugees. For example, according to Jochen Frey, spokesman of the car maker BMW, when it comes to missing documents about vocational qualifications,

what ultimately decides is what a person can do, and not what is on paper … In the auto company, several refugees have now started a vocational training. “We have had very good experiences here, the motivation is very high,” says Frey. Many bring craftsmanship skills, practical work is easy for them.

This optimistic evaluation fits into many people’s ideas about the refugees, after having fled desperate circumstances, gratefully grabbing the opportunities offered for them in Europe.

Alas, later reports about the motivation of refugees in vocational courses were far less enthusiastic. For example, in 2017 the newspaper Die Welt published an article with the title Refugees don’t fit into the German vocational training system. The newspaper wrote:

The often-told success stories of young refugees who are successfully completing their training as bakers or joiners in this country are still isolated cases. Even though there is an oversupply of training places in many regions in Germany, the majority of the refugees do not find one.

Many companies in Germany were – and still are – desperate to find skilled workers and were prepared to give a chance to refugees and train them.

Knowing that close to 80% of the refugees had no occupational qualifications, one would imagine that a large percentage of the more than 1.5 million refugees who arrived since 2015 would eagerly want to participate in vocational training.

Instead, at the time the article was written, in 2017, only 25,000, a small percentage of all refugees, were registered at job centers and employment agencies as interested in vocational training.

The wording used in the above article – that the “majority of the refugees do not find” a training place – is not accurate. What apparently often happens is that they break off the training, sometimes after only a few days. The newspaper Die Welt writes in an article in 2015:

Around 70 percent of the trainees who fled Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq and began their apprenticeship in September 2013 have now broken off their training without a degree, said the Managing Director of the Munich Chamber of Crafts and Upper Bavaria, Lothar Semper.

There have been many similar reports. For example, the newspaper ÄrzteZeitung, a paper for medical professionals, contained an article in 2019 with the heading:

Many young refugees drop out of nursing education.

Out of 25 refugees who participated in a nursing education project, only eight are still around.

Or the headline of an article from Hamburger Abendblatt from 2016:

Every second refugee drops out from vocational training.

What are the reasons for these high dropout rates?

One reason often mentioned is the lack of German language skills. Another reason is lack of relevant education: even if they had a degree, it was not comparable to a degree in Germany. For example, Islam education took up a lot of space in the curriculum.

A further reason is the expectations of the refugees: based on their experiences in their home countries, they can’t see why the have to have a long course of study, to be trained, for example, as a hair dresser or car mechanic. Also, the reputation of vocational training in their countries of origin is traditionally often low, as compared to a college study.

Furthermore, many refugees have a short-term perspective: though they receive money for participating in a vocational training, it is a lower amount than a real salary. They don’t see that investing time and effort into a training program increases their chances to earn better money later.

Finally, an anecdotal description of the situation from a user comment below a newspaper article:

We had it here in our factory: refugee from Pakistan, according to the boss well trained. On the 4th day already too late to work; just stayed home after 6 days; last seen after two weeks. After that he never showed up again.

Language skills training in Germany

As mentioned above, one of the main reasons for refugees dropping out of vocational training courses is lack of German language skills. Thus, one would imagine that they would grab every opportunity to learn the language.

And there are opportunities offered to them: the German Federal Government supports integration courses and language courses:

Language and integration courses are an offer to all immigrants in Germany. Anyone who is a recognized refugee, for example, has the right to an integration course paid by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) – but also the obligation to participate if the language skills are insufficient … 600 hours are planned for the German language in the integration courses. Five times a week and four hours a day.

Large sums of money flow into these courses. According to the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, writes the German newspaper Die Welt in 2019,

the Federal Government has spent around 3.39 billion euros on integration courses since 2013. The majority of this amount is spent on language courses.

What use do the refugees make of these courses? The results are not very encouraging: only 25% of Eritreans and Somalis and about 30% of Iraqis, Syrians and Afghans pass the intermediate German language test Level B1. Passing this test shows

that the person can, for example, sustain a conversation and express in everyday situations what he wants to say.

This situation seems to be getting worse:

In general, the proportion of participants who do not reach the B1 level has risen over the past few years. The main reason for this is that the proportion of people who have to learn to read or write completely or largely has increased, said the ministry.

An article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from 2018 is similarly pessimistic about the results of the language tests:

According to the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (Bamf), 339,578 people visited an integration course for the first time last year [in 2017]. However, significantly fewer, namely only 289,751 foreigners, later participated in the language test at the end of the course. Of those who even participated in the language test, not even one in two (48.7%) achieved the target level B1. Four out of ten (40.8%) only reached the lower level of A2, with the rest below that. In 2016 it looked similarly bleak: Almost 340,000 people took part in an integration course, only about 100,000 passed the test at the B1 level.

About the Level A2 a Green Party member of the Parliament says this:

The level A2 is often not enough for the entry into training and work.

What are the reasons for these problems?

Typically, the reasons given by officials often try to excuse the refugees and blame the system of the language courses and society in general instead:

The Bamf points out that some participants become ill during the course, others find or move to work and therefore fail to take the final exam. The well-meaning headmaster of a large community college answers that the goals are too high and society should have more patience. Many immigrants were traumatized by the escape and therefore could not learn so well. Others lack a “learning culture”. They did not attend school in their home country and had no technique for learning foreign vocabulary and grammar.

The article gives an alternative explanation for the bleak results of the language courses:

A more critical look shows that many refugees skip too many hours in their language courses. This is also stated in a report of the Federal Court of Audit. The officials had checked language courses of the Federal Employment Agency – and came to a disastrous result a year ago. “It can be assumed that a large part of the funds spent was lost, because the courses were characterized by dwindling numbers of participants,” says the final statement to the Executive Board of the Federal Employment Agency. Specifically, in “almost all” of the 528 courses there were less and less participants as the course progressed.

Some participants of the Federal Employment Agency courses were interviewed for the article. One of them reported that

twelve people were enrolled in her course. “Only two were always there. Two or three people were mostly there, and the rest was almost never in the class. It was almost like private lessons”. Sometimes the teacher called the missing people. They would then have signed their names into the presence list – and went home again. “My feeling was that most people did not care about the course at all. And on the last day, when we were taking the exam, the people who were never there signed their names in the list for the past weeks”.

So why do many of the migrants skip classes, break off the courses prematurely, or don’t appear for the final test? An opinion piece in the Die Welt newspaper tries to give an answer: many refugees consider the language courses a “waste of time”.

“We will never need that”, say especially older men. “We want to work, but you do not need German for that”, they think. This attitude is difficult to crack. Africans, in turn, believe that they do not have to learn German because they speak the world language English. When a patient refugee helper asks them if German colleagues should learn English for them, some of them become thoughtful.

At one point the article asks:

How do you teach German to these people if they do not recognize the value of it, even though its mastery can improve their progress exponentially?

Some reasons for optimism

In spite of the many problems mentioned above, one could expect that some of these problems might disappear or will be less with time. After all, many of the refugees have been in Germany only for a few years. One would hope that, in time, living in Germany will change the mentality of many refugees so that they get used to the norms and expectations in the country. Sooner or later many will receive some vocational training, and the longer they are in the country, the better their language skills will become.

There are some positive news already. For example, even though the above mentioned number of 25,000 refugees interested in vocational training in 2017 is small as compared to the number of all refugees, this was three times the corresponding number from 2016. Also, though the vocational training drop-out rate for refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq in the article quoted above was around 70%, the drop-out rate for refugees from other countries was lower: 25%.

There are also reports which quote lower rates of dropout from vocational training than those mentioned above. For example, a report in 2017 by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry for the city Oldenburg states a dropout rate of about 20% for refugees – which is only slightly more than for apprentices born in Germany.

If they start having families, their children will receive the same level of education and the same chances in Germany as children of German families. Also, one of the main factors holding back the refugees – lack of language skills – will be less of a problem for their children. Thus, though many of the refugees have only primary school education or none, their children will be far better educated and will have much better chances to get better jobs than their parents.

Thus, one can expect that in the long run the refugees and their families will be increasingly integrated into the German economy.

Long term educational prospects

What happens to the refugees in the long term?

Many or most of the refugees who have arrived in Germany want to settle in Germany or possibly in some other European country. After they are recognized as refugees, they can stay in the country, and can even bring their relatives in a process of family reunion.

What happens to those who are not recognized as refugees, for example because their home countries are deemed safe?

Many of these don’t have (or claim not to have) passports, and they receive a so-called “toleration” (Duldung in German). For example, in February 2019

around 240,000 people were supposed to leave Germany. However, 184,013 of these rejected asylum seekers possessed “toleration”.

About half of these “tolerated” people claimed that they didn’t have passports. Others were “tolerated” for medical or other reasons. Whichever the reason, “tolerated” refugees are allowed to stay in the country. Though “toleration” is supposed to be temporary, many of them continue living in the country permanently.

There are also some attempts to deport them back to their countries, with around 23,000 yearly over the last few years. Others leave the country voluntarily.

All in all, whether recognized as refugees or not, most of those who apply for asylum in Germany, will stay there permanently. Their educational level, occupational qualifications, language skills will have an effect on their lives in the country. Given their large – and growing – numbers, these will affect German society, too. Thus, it would be important to keep track of the educational development of refugees and their children. The three-yearly PISA tests provide an opportunity to do this.

PISA 2015

The following is from a description of the PISA programme, on the web site of the OECD:

PISA is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment. Every three years it tests 15-year-old students from all over the world in reading, mathematics and science.

The latest PISA tests were carried out in 2018 but its results will not be available until December 2019. The latest available PISA test results are from 2015.

The test is carried out in a large number of countries. In addition to the test results, many other variables are recorded, among them whether the participating students have a migration background or not. A student has “migration background” if his/her parents were born in a foreign country. Thus, there are “first generation” migrants (who, like their parents, were born in a foreign country) and “second generation” migrants (who were born in the new country). Children of “second generation” migrants” – belonging to the third generation – don’t count as having a “migration background” any more.

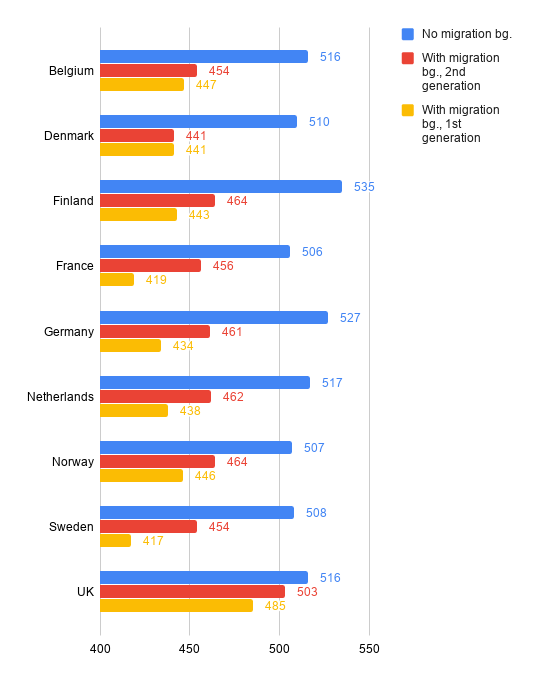

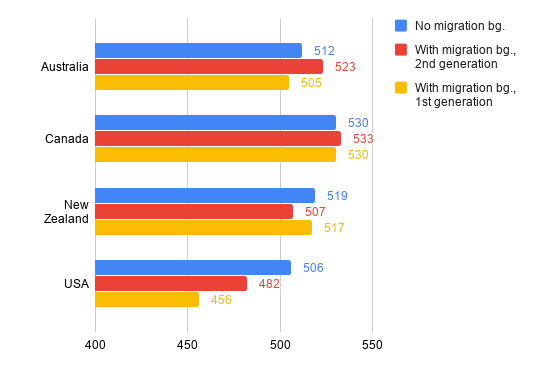

The following chart is based on a study which analyzed the PISA 2015 results. The chart shows the result scores for the “science” questions for a number of Western European countries (p. 455 of the study). The countries in this list have been the target of migration for the last few decades. The PISA scores are broken down by migration background: students with no migration background, and those with second and first generation migration background.

On average, there is a 75 point difference between the students with no migration background and those with a first generation migration background. This gap decreases to 54 points for students with second generation migration background.

The scores for the UK look different, possibly explained by the fact that a large percentage of recent immigration to the UK is from other European countries like Poland and Hungary. Another explanation could be that immigration to the UK from other parts of the world is more selective. This is what the Pew Research Center assumes about Muslim immigration to the UK (see later in this article). In contrast, a large percentage of immigration to the other countries in the chart are from the Middle East, Central- and South Asia, and Africa and immigration is much less selective.

For comparison, the following chart shows the PISA 2015 “science” results for a number of traditional immigration countries.

This chart shows that the type of immigration matters a lot with regard to the PISA results.

The gaps between the students with no migration background and those with a migration background are far smaller in this case (and in the case of Australia and Canada there are gaps in the reverse direction). This can be explained by the fact that immigration policy in the first three countries (Australia, Canada and New Zealand) is very selective and focuses on skilled and professional immigrants – in contrast to the European countries in the chart above.

In the case of the USA the pattern of the PISA results resembles the European pattern. This could be explained by the fact that the migration patterns are similar: both Western Europe and the USA has experienced large scale immigration from the third world – in the case of the USA from Latin America.

One could hypothesize that, given the relative poverty of the people with migration background in Europe, the gaps in Europe are simply the result of worse socioeconomic circumstances. The data shows that these indeed play a role. However, after taking the socioeconomic situation of the students into account, in most cases 50 to 70 percent of the gap between the “no migration background” and “second generation migration background” students still remains (p. 456 of the PISA 2015 study).

Another hypothesis could be that the gaps in Europe are caused by the fact that even students with “second generation migration background” might speak a foreign language at home – and thus their language skills are worse than the language skills of those with “no migration background”. The gap does decrease if the student “with migration background” speaks the language in which the test was administered, i.e. the language of the country the student is living in (e.g. German) as compared to the language of the parents (e.g. Arabic) – but 70 to 90 percent of the gap still remains (p. 461-462 of the PISA 2015 study).

What can be expected in the long term? Will these differences decrease and eventually disappear between Europeans having no migration background and those with a migration background? Or will a gap remain in the long term?

The gap can decrease for two reasons: either because there is genuine improvement in the test results of the “migrant background” population, or because there is a decline in the test results of the “no migrant background” population. Combinations of these two reasons are possible as well.

A second reason might need some explanation: if mass migration from the third world continues to Europe and at the same time the European native populations continue shrinking, then the share of third and later generation descendants of migrants will grow in the “no migration background” population. The gap between the two groups will decrease because they will be more and more similar to each other.

With the continuous supply of low education migrants provided by mass migration, it seems probable that the gap will decrease for the second reason, by decreasing the PISA results of the “no migration background” population.

How will the total PISA results of European countries – containing both non-migration and migration background students – be influenced by mass immigration over the long term? Based on the above considerations, we could formulate these two hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: the PISA scores of countries with high levels of third world immigration will decrease in time.

- Hypothesis 2: the PISA scores of countries with low levels of third world immigration will decrease less than for countries with high levels of third world immigration or they stay the same or will even increase.

PISA 2003-2018

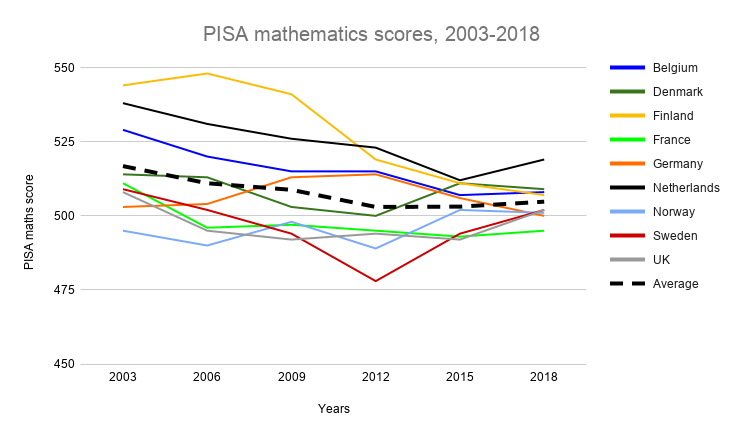

Looking back at past PISA test results might give a hint about what we can expect in the future. The PISA results since 2003 show a general downwards trend until 2015 for mathematics scores for the Western- and Northern European countries considered above, as the chart below shows.

In 2018 there was a slight improvement in the average results. This improvement is mainly driven by large improvements in the UK, in Sweden and in the Netherlands.

These improvements clearly contradict Hypothesis 1. Sweden, in particular, has experienced large numbers of refugees entering from the third world, while its mathematics scores have improved a lot over the last two PISA tests.

Notice one thing though: participating countries could exclude some students from the tests, for example because of lack of language knowledge or intellectual disability. There was an exclusion rate limit set to 5%, but some countries, including Sweden, had higher exclusion rates that that limit. Sweden, in fact, had the highest rate of exclusions among all countries: 11.1%. This is what the 2018 PISA report says about these exclusions:

It is believed that this increase in the exclusion rate was due to a large and temporary increase in immigrant and refugee inflows, although because of Swedish data-collection laws, this could not be explicitly stated in student-tracking forms.

PISA 2018 Results, WHAT STUDENTS KNOW AND CAN DO, VOLUME I, p. 160.

This high Swedish exclusion rate was accepted by PISA as “non-biased”, but the reasons given above for the Swedish exclusions allow doubts about the validity of the Swedish performance increase.

Notice also that Netherlands and the UK – also with large increases in the 2018 results – had larger than 5% exclusion rates, too. On the other hand, Belgium, Finland, Germany, France had lower than 5% exclusion rates and experienced in 2018 either a drop or only a very small increase in mathematics performance. But then again, Denmark and Norway also had exclusion rates higher than 5% and they experienced a slight decrease.

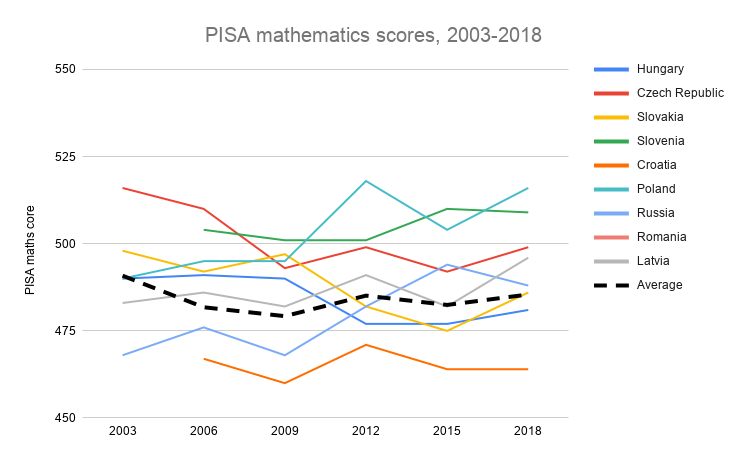

The average mathematics test results for these countries show a drop in performance since 2003, which supports Hypothesis 1.

The PISA results of countries with low levels of third world immigration (see the graph below) show a complicated picture, too. Just as in the Western and Northern European countries, in these countries – most of which are in Eastern and Middle Europe – there is a slight recovery of the average mathematics test results in 2018, though they still don’t reach the level in 2003. All in all, average mathematics test performance shows a smaller drop between 2003 and 2018 – and a larger recovery in 2018 – than for the Western and Northern European countries.

Note also that the exclusion rates in none of these countries are above 5%. All this supports Hypothesis 2.

Clearly, the results are complex, and though there is some support for Hypotheses 1 and 2, there are very probably many factors other than immigration (or the lack of it) which played a role.

At this point we can not tell with any certainty how mass immigration influences the PISA results. A more thorough statistical analysis, using also migration and other data, would be necessary. Future PISA test results might also give much relevant information.

However, there is another reason to assume that the European PISA results will decrease in the future if current mass migration trends continue: different ethnicities/races and cultural groups are not equal with regard to cognitive abilities.

The role of IQ

The standard way of measuring cognitive abilities are IQ tests.

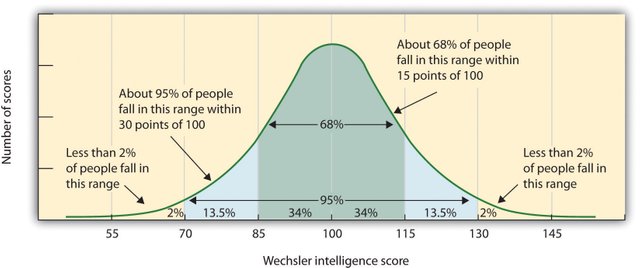

IQ tests contain a number of sub-tests, and the results on these are combined into a single number, the Intelligence Quotient (IQ).

Over the years the average IQ of populations in many countries was measured. IQ follows a bell-shaped, normal distribution, with the average IQ at the peak of the distribution. 50% of the population is above and 50% is below the average. In the figure below the average IQ is 100.

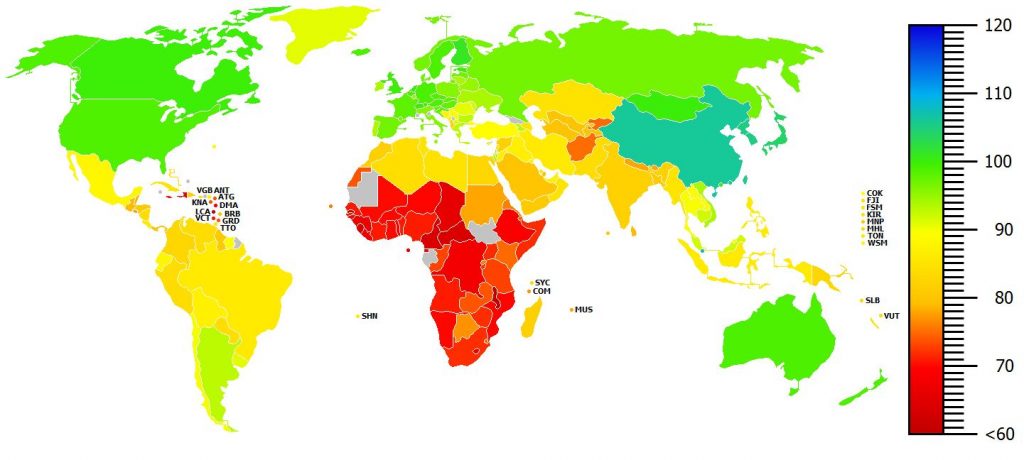

The following map is based on the results published by Lynn & Vanhanen (2012). The map shows IQ levels calculated from psychological IQ test results plus international school assessment studies. If not enough data was available for a country, its IQ level was assessed based on the IQ’s of the surrounding or ethnically similar countries.

The right hand vertical color bar shows IQ levels, starting at < 60 at the bottom and ending with 120 at the top. Thus, the more red a country is colored, the lower the IQ is in that country, and the more green (towards blue) a country is colored, the higher is the IQ there.

The highest average IQ values – around 105 – were measured in North Eastern Asian countries (China, South Korea, Japan).

The European average IQ is around 100, with Southern and Eastern Europeans having somewhat lower values. The IQ in North America, Australia and New Zealand is similar to the European IQ.

In North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia the average IQ is between 80 and 90.

In countries of Sub-Saharan Africa the average IQ is between about 70 and 80. In fact, Lynn & Vanhanen (2006) proposed an average IQ value of 67.

Lynn & Vanhanen’s work – in particular their methodology, their data sets and the low estimates of African IQ – was heavily criticized. For example, Wicherts, Dolan & van der Maas (2010) asserted that their African IQ estimate is too low: after a review of the literature they concluded that the correct value is 82. Lynn & Meisenberg (2010) answered their criticism by writing that the IQ estimate by Wicherts, Dolan & van der Maas (2010) was based on unrepresentative elite samples. However, they increased Lynn’s original Sub-Saharan African IQ estimate from 67 to 68.

In spite of such criticisms, the work of Lynn and his co-workers have been taken seriously by many scholars (e.g., Jones, 2018; Palairet, 2004 ). Their work has been published many times in peer reviewed journals like Intelligence. It provoked many discussions and led to new research. Also, their work is still the most comprehensive comparison of IQ differences between nations.

The data they gathered is also highly relevant to Europe’s migration issues. Much of the immigration to Europe comes from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In both the Middle East and in Africa the population grows very fast. In Africa the current population of about 1.2 billion will double by 2050, according to UN estimates.

Already now there is a large migration pressure from Africa and the Middle East towards Europe and given the population explosion in these regions, the migration pressure will very probably increase further. More people will try to enter Europe from these regions in the future.

Effect on European IQ

How will this influence the average IQ in European countries in the future? There is not much doubt that in the short and medium term it will tend to decrease the European average IQ. In the long term, we think that the effect will depend on how far the IQ of the incoming migrants can be increased through measures like education, better socioeconomic circumstances and better nutrition.

Cognitive abilities can be increased by environmental interventions like better nutrition and education. For example, Lynn (1999) argued that the Flynn effect – the increase of IQ by about 3 points per decade since the 1920s – could be due to generally improved nutrition.

In the US, there have been a number of projects aimed at improving the education level and cognitive abilities of underprivileged (often black) children at an early age. The Perry Preschool Project is an examples of such projects.

According to the Perry Preschool Project , there were large benefits, some of them reaching into adulthood of the children: less crime, more stable family life, higher income. There were also increases in measured IQ, as compared to a control group.

But, similarly as in other early intervention projects – like the Milwaukee Project and Head Start – the increase in IQ was maintained only while the children were treated intensively in the projects and it declined after the children left the projects.

One important factor to consider is that there is now much evidence that IQ is heritable to a large extent. The heritability is about 0.5, on a scale between 0 and 1 (Plomin, 2018). Some other heritability estimates are higher, up to 0.8 (Gottfredson, 1994).

This does not necessarily mean that the differences in average IQ between Europeans and African or Middle Eastern migrants are based in genetics – they could be, in principle, fully caused by lower educational experiences or worse nutrition of the migrants.

However, there is evidence that the difference is in fact – at least partially – caused by genetic factors.

For example, brain size correlates positively (though modestly) with IQ (Haier, 2016, p. 84). Brain size is highly heritable (Posthuma et al., 2002), thus determined to a large extent by genetic factors. There are differences between the brain sizes of different populations: for example, average brain size is smallest for African-Americans, medium size for European Americans and largest size for East-Asian Americans and these differences follow their IQ differences (Rushton & Ankney, 2009).

All this speaks for a genetic influence on the IQ differences between populations.

All in all, although part of the IQ gap between Europeans and migrants can be removed by different interventions, skepticism is justified regarding the possibility of a full removal of the gap. Thus, it is probably inevitable that mass migration will cause some decrease in European IQ. Furthermore, intervention measures will only work, even partially, if the European educational and other institutions are not overwhelmed by continuing mass migration.

IQ and society

Not surprisingly, IQ has a large effect on educational success. Rindermann (2007) analyzed the PISA 2000 and PISA 2003 results and correlated them with the national IQ data from Lynn & Vanhanen (2006). He found very high positive correlations between the PISA and national IQ results, between 0.84 and 0.89 (on a scale between -1 and 1).

Roger Titcombe calculated the correlation between an updated set of national IQ values (Lynn & Vanhanen, 2012) and the PISA 2015 mathematics results. The correlation was positive and very high: 0.89.

Thus, higher IQ predicts higher PISA results and lower IQ predicts lower PISA results. Consequently, if the average European IQ decreases as a result of mass immigration from the third world, we can expect lower European PISA results – and thus lower levels of education – in the future.

This will very probably have a negative effect on European societies of the future which are becoming increasingly high-tech- and knowledge-based. How will Europe compete in the future with countries like Japan, China and Korea which have, already now, higher national IQs than any European country and which reject mass immigration? Or with countries like Canada and Australia which have a selective immigration system?

In addition to the above, IQ also correlates with some other important societal factors, like

- Cooperation

- National savings

- Government quality

- Low corruption

- Productivity of society

- Prosperity of society

Low national IQ predicts lower levels of cooperation, lower national savings, lower quality of government, higher corruption, lower productivity and lower prosperity of a nation (Jones, 2018).

These are some of the effects on society that European countries might experience in the future, as a result of mass immigration.

As German journalist and author Peter Scholl-Latour apparently said once:

If you take in half Calcutta, you will not save Calcutta but you’ll become Calcutta.

Peter Scholl-Latour (1924-2014), German journalist and author

Religion, cognitive abilities and education

Psychologists have researched the relationship between religiosity and intellectual abilities for decades. They generally found a negative correlation between religiosity and intellectual abilities (Stoet & Geary, 2017).

Stoet & Geary (2017) compared national levels of religiosity with educational performance on TIMMS (Trends in International Mathematics

and Science Study) and PISA tests for three time periods (2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2015). They found:

In three time periods between 2000 and 2015, higher national levels of religiosity were consistently associated with lower national levels of science and mathematics achievement.

What does this mean for the European migration situation?

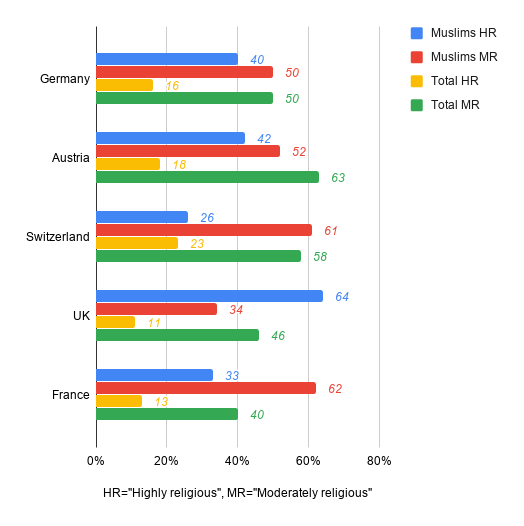

The large majority of the recent mass migration wave into Europe are Muslims. On average, Muslims are far more religious than Europeans. The German Bertelsmann Stiftung surveyed Muslim religiosity in 2017 in five European countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, UK and France). More than 10,000 people altogether were surveyed. The results are shown below.

The chart depicts the percentages of Muslims and of the general population who describe themselves as “highly religious” vs. “moderately religious”.

According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s data, a lot more Muslims describe themselves as “highly religious” than the rest of the population, in every one of the five countries, except in Switzerland where there is only a small difference. The difference between Muslims and the rest of the population is particularly striking in the UK, where almost 6 times more Muslims describe themselves as “highly religious”. The Bertelsmann Stiftung’s report concludes:

Overall, Muslims from immigrant families maintain a strong religious commitment. Unlike among many non-Muslims, this connection is likely to continue across generations.

In fact, in some European countries there is a tendency towards increased religiosity and Islamic radicalization among young Muslims. This report is from the German newspaper Die Welt, from 2018:

In October 2017, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) reported a new phenomenon: in the past months, the Radicalization Hotline of the Office had been increasingly called by teachers and school psychologists who had noticed primary school children with Islamist tendencies, so-called Children of Salafism.

“Most children have their socialization from a Salafist environment – that is, the parents themselves are already radicalized,” said Florian Endres of the Advisory Center radicalization in Nuremberg.

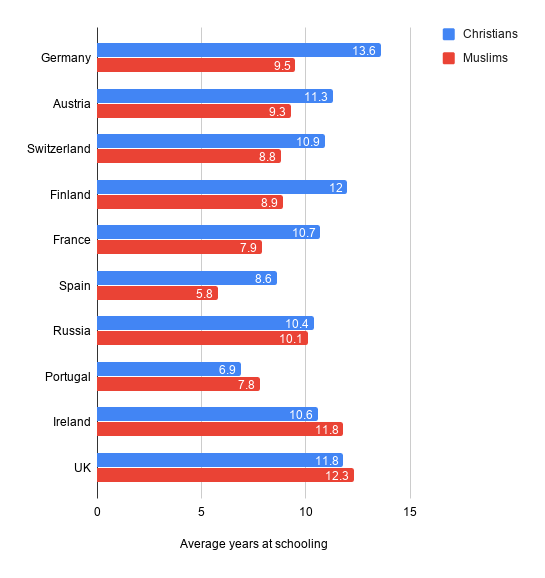

The following chart shows the average number of years spent at school for a number of European countries, for Christians and for Muslims. The source is a survey by the Pew Research Center from 2016.

Muslims in Europe spent less years at school than Christians in the majority of the countries.

On the other hand, the Pew Research Center report notes that in several countries there has been an improvement in the number of school years of young Muslims. Thus, while in Germany the gap between Muslims and non-Muslims in general is 4.1 years,

among the youngest generation [it] is only about two years of schooling, on average (12.5 years vs. 14.5 years).

Notice also that in a number of countries – UK, Ireland and Portugal – Muslims have a lead over Christians regarding the average number of school years. This is how the Pew Research Center report explains this lead:

In countries with relatively high education levels among Muslims, such as the United Kingdom and Ireland, Muslim communities often have been shaped by immigration policies favorable to highly educated migrants.

There is a further question, in particular about schools in the UK: what do Muslim children learn during those years at school? Some pupils go to schools run by Islamic organizations, which got into trouble in the past for segregating boys and girls. Others go to state schools in parts of the UK with a high Muslim percentage, like in Birmingham, where, as reported by the UK newspaper Telegraph in 2014,

the National Association of Head Teachers has expressed deep concern over a fundamentalist agenda to drive out secular or moderately religious Birmingham school heads and replace them with those who support policies such as sex segregation and exaggerated adherence to religious edicts that heavily restrict teaching.

This so called “Trojan Horse” incident prompted an investigation of 16 state schools in Birmingham by the UK Government.

by the UK Government

The report of this investigation found

plenty of evidence of “non-violent” extremism: Muslim children being warned not to listen to Christians because they were “all liars”, how they were “lucky to be Muslims and not ignorant like Christians or Jews”, how they would go to hell if they did not pray.

There was also evidence of segregation, homophobia, a hard-line curriculum, contempt for the armed forces and even scepticism about the truth of reports about the near-beheading of Drummer Lee Rigby and Americans killed by the Boston nail bombers, and “a constant undercurrent of anti-western, anti-American and anti-Israeli sentiment”.

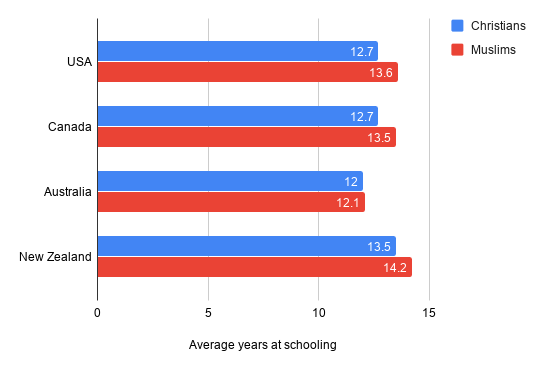

In countries with selective immigration systems – the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – Muslims have higher numbers of school years than Christians, similarly to the UK and Ireland:

The Pew Research Center report says:

large majorities of … Muslims were born outside the United States.

It seems that most or many of these highly educated Muslims have acquired their education in their countries of origin. Given the low educational levels in all Muslim majority countries (see the Pew Research Center report), these people were an elite group and were allowed to immigrate to the US probably because of that. Their high numbers of school years is not representative of Muslim populations in general.

Thus, in spite of these cases of Muslim populations with high levels of education, and signs of the gap between non-Muslims and Muslims decreasing, the high and enduring levels of religiosity of Muslims, the negative link between religiosity and cognitive performance, the low educational performance of Muslims in many European countries, and the influence that fundamentalist Islam has on the content and methods of teaching Muslim students, advises caution about the mass immigration of Muslims to Europe.

Summary

After the euphoric announcements about supposedly highly educated refugees streaming into Europe in 2015, very soon a disillusionment followed: it became clear that large numbers of the refugees had very little education and very few job qualifications. European states – in particular Germany – have invested huge amounts of money and huge efforts into trying to educate these people, teach them the language of the country and give them vocational training.

Some of these efforts at integrating these people succeeded and are having positive effects. But many others were not very successful and some of them failed dismally.

Thus, there are worrying signs for the future. Did Europe import – and is continuing to import – a large permanent under-class of people with relatively low levels of education, limited cognitive abilities, but high levels of Islamic religiosity? How will this influence Europe’s human capital in the long term? How will it affect European economic productivity – and its ability to compete with the highly dynamic, highly intellectually capable East-Asian nations which reject multiculturalism and with other Western countries which subscribe to a selective immigration policy? And finally, how will it affect the very substrate of European societies – their democratic institutions, their rule of law, their relatively low levels of corruption?

Literature

Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Mainstream science on Intelligence: An Editorial with 52 signatories, history and bibliography. Intelligence 24(1) 12-23.

Haier, R. J. (2016). The neuroscience of intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, G. (2016). Hive mind. How your nation’s IQ matters so much more than your own. Stanford California: Stanford University Press.

Lynn, R. & Becker, D. (2019). The Intelligence of Nations. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Lynn, R., & Meisenberg, G. (2010). The average IQ of sub-Saharan Africans: Comments on Wicherts, Dolan, and van der Maas. Intelligence 38 (2010) 21–29.

Lynn, R., & Vanhanen, T. (2006). IQ and global inequality. Augusta (GA): Washington Summit.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2012). Intelligence: A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Nyborg, H. Ed. (2013). Race and sex differences in intelligence and personality. A tribute to Richard Lynn at 80. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Palairet, M. R. (2004). Review of IQ and the Wealth of Nations. Heredity, 92, 361-262.

Plomin, R. (2018). Blueprint. How DNA makes us who we are. Allen Lane.

Posthuma, D., De Geus, E. J., Baaré, W. F., Pol, H. E. H., Kahn, R. S., & Boomsma, D. I. (2002). The association between brain volume and intelligence is of genetic origin. Nature Neuroscience, 5(2), 83.

Rindermann, H. (2007). The g-Factor of International Cognitive Ability Comparisons: The Homogeneity of Results in PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS and IQ-Tests Across Nations. European Journal of Personality 21: 667–706 (2007).

Rushton, J. P., & Ankney, C. D. (2009). Whole brain size and general mental ability: a review. International Journal of Neuroscience, 119(5), 692-732.

Stoet, G. & Geary, D. C. (2017). Students in countries with higher levels of religiosity perform lower in science and mathematics. Intelligence 62 (2017) 71–78.

Wicherts, J. M., Dolan, C. V., Carlson, J. S., & van der Maas, H. L. J. (2010). Raven’s test performance of sub-Saharan Africans: Average performance, psychometric properties, and the Flynn Effect. Intelligence 38 (2010) 1–20.

To be continued.

Be the first to comment on "The Great Replacement: Myth, conspiracy theory, or reality? Part 4: “What they bring us is more valuable than gold”"