Europe’s population is shrinking because of falling birth rates. This is a serious issue, affecting not only Europe, but the whole of the Western world, plus East Asia, and even Eastern European countries like Russia. It is to be expected that, if nothing is done about this, it will have a negative effect on the economical development of these countries. As an article in Foreign Policy writes:

This is cause for concern, because low [birth] rates, as the political economists Nicholas Eberstadt and Hans Groth have pointed out, often “portend ominous change in economic prospects [for countries]: major increases in public debt burdens, and slower economic growth,” because they eventually lead to a shrinking workforce.

If one asks, would it not be an alternative to try to increase the birth rate of European populations, the answer is often that the cost-benefit ratio for that is not economical. In addition, as the media sometimes hints, attempts at increasing the birth rate of Europeans – instead of increasing immigration from Africa or the Middle East – is seen, except in Hungary, almost as a sign of racism, similar to what the German Nazis did to increase the German population.

Being accused of racism is of course one of the worst things that can happen to a centrist EU politician nowadays. Thus, there is not even a discussion, either in the mainstream media or in politics, about how to increase birth rates. It is simply assumed that immigration is the only way to solve these issues.

So, let’s take a look at the cost-benefit ratio of European immigration policies. The main origin of mass immigration to Europe is the non-Western world – mainly Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. Many of these immigrants arrive as “refugees”. This type of immigration will almost certainly increase in the future, given the helplessness and incompetence of EU policies and the huge population increase to be expected in Africa and the Middle East in coming years and decades.

Financial cost of “refugees” in Germany

So how much does non-Western immigration cost Europe? An article from 2017 in the Swiss daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung discusses this, in the context of “refugee”-based immigration to Germany. The article says:

The refugee costs are spread over many budgets. Anyone who asks the Berlin government for the total amount is sent into a labyrinth of statistics and responsibilities. Only one decisive number does not exist: that of all expenses for a clearly defined group of people.

The article continues:

After all, it is not about trifles, but huge budget posts. The federal government alone wants to provide 93.6 billion euros to supply the refugees from 2016 to 2020. Since the federal states complain about getting reimbursed at most half of the costs, the annual estimate would be between 30 and 40 billion. It remains unclear whether the additional expenditures for 180 000 new kindergarten places, 2400 additional primary schools and the promised 15 000 police officers are included.

It also remains unclear if the many costs related to crimes committed by the refugees are included. That these are probably significant sums is shown by the number of crimes committed by refugees. As an example, in 2018 almost 300,000 crimes were cleared up with refugees as suspects. Given that the only about 50% of crimes are cleared up, the actual number of crimes must be a lot higher than 300,000.

The administrative courts alone demand 2000 more judges to handle the asylum wave, which has quadrupled since 2015 to 200 000 court cases.

Health related costs should also be included:

The Robert Koch Institute in turn points to a drastic increase in dangerous infectious diseases such as tuberculosis or AIDS, which have come with the refugees into the country.

So how much would this be altogether?

The Institute of German Business (IW) comes to the amount of 50 billion, the same amount that has also been calculated by the Council of Economic Experts for 2017. The Kiel Institute for Economic Research calculates with up to 55 billion euros per year.

How does this compare to the German federal budget?

This is about as much as the budgets in this election year [2017] of the Federal Ministries of Transport (27.91 billion), Education and Research (17.65 billion) and Families, Women, Senior Citizens and Youth (9.52 billion) taken together. In other words … each person seeking protection in Germany costs 2500 euros per month … For an unaccompanied juvenile migrant even up to 5000 euros per month are estimated.

It is not clear for how many years the German state needs to pay these amounts per refugee. After all, “unaccompanied juvenile migrants” will also grow up to become adults, and many refugees will find work after some time – though many others will remain unemployed or under-employed and many will bring their families to Europe. So what would be the cost-benefit calculation for Germany for taking in a refugee?

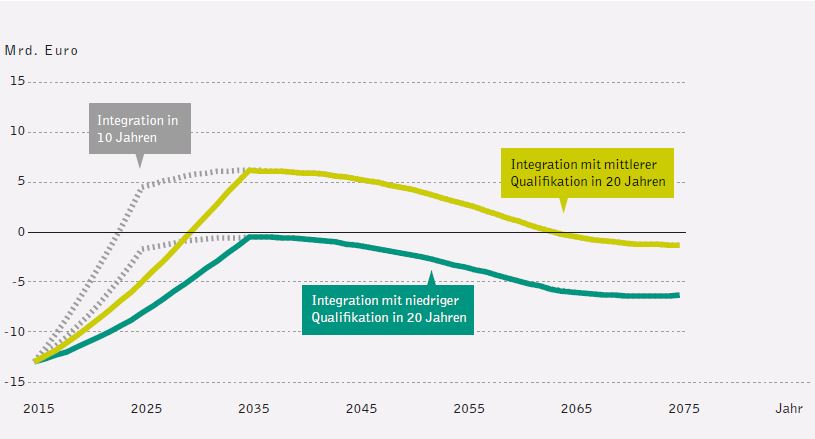

Bernd Raffelhüschen, a German financial scientist, did some calculations in 2015. His calculations were based on the about 1 million refugees who were in Germany in 2015. The following chart shows part of his results:

Green line: integration with low qualification in 20 years,

Grey broken line: integration in 10 years.

The chart shows that, under the assumption that the refugees, on average, are integrated into the labor market in 20 years and will have a medium qualification (yellow line), one can expect net positive financial contributions from them from about the year 2030 on. If the average qualification is low (green line), then the refugees will have only a negative net contribution over their whole life time.

Given the initial low qualification of most of the refugees and the low efficiency of the attempts to try to integrate refugees into the work force (training, language courses, etc.), as described in Part 4 of this series, the first scenario is not very realistic. The most realistic scenario is probably somewhere between the two lines in the chart above, and thus it is quite probable that the overall net contribution of the refugees will be negative in such an in-between scenario as well.

An article in the German newspaper Die Welt writes:

According to Raffelhüschen calculations using the “net present value method”, which includes all spending and social security over the lifetime of a refugee, the costs adds up to a horrendous sum: even with an integration of immigrants in the labor market within six years, the additional costs amount to 900 billion euros in the long term.”

It should be noted that Raffelhüschen assumed a cost of 17 billion euros per year, caused by the 1 million refugees – which is a lot less than the estimates by the Institute of German Business (50 billion euros per year) or by the Kiel Institute for Economic Research (55 billion euros per year).

Furthermore, Raffelhüschen’s calculations were restricted to the around 1 million refugees in 2015. Since then at least one million more have arrived. Although the numbers continuously decreased since 2016, it is very probable that they will increase again, given the population explosion ongoing in Africa and the Middle East. Thus, if there is no change in German policies, then we can probably expect a lot higher cost than the 900 billion euros calculated by Raffelhüschen.

Net financial contributions of non-Western immigrants in Denmark

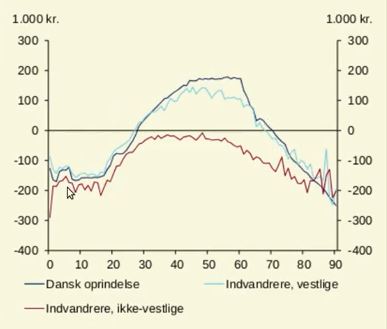

Danish researcher Emil Kierkegaard calculated the net contribution of non-Western immigrants to Denmark, based on Danish population registry data. The charts below are from Dr Kierkegaard’s Google presentation document.

The following chart shows the net contribution for Danish society for the life time of three groups: native Danes (dark blue line), Western immigrants (light blue line) and non-Western immigrants (red line).

native Danes (dark blue line), Western immigrants (light blue line), non-Western immigrants (red line)

The chart shows that, on average, over their whole lifetime non-Western immigrants have a net-negative contribution: they cost the state more than they contribute (in contrast to native Danes and Western immigrants, who contribute more than they cost the state).

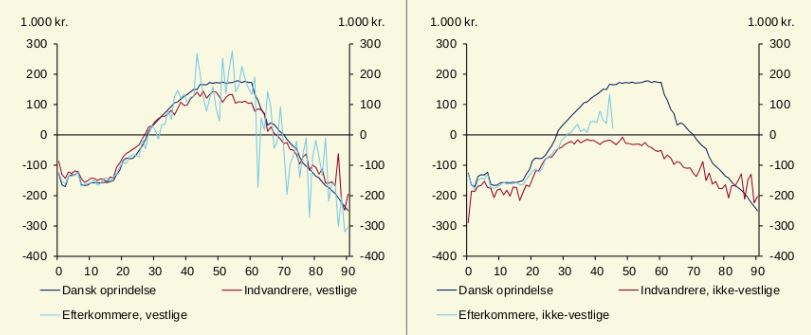

Note that the “immigrants” in the chart above refer to first-generation immigrants. As shown in the charts below, children of non-Western immigrants (light blue line in the right hand part of the picture) have a net-positive contribution from about the age 30, but remain under the contribution of both native Danes and of the children of Western immigrants – and, though the data is not fully available to say this with certainty, their net contribution, summed up for their whole life time, is negative.

Native Danes (dark blue line), children of immigrants (light blue line), immigrants (red line)

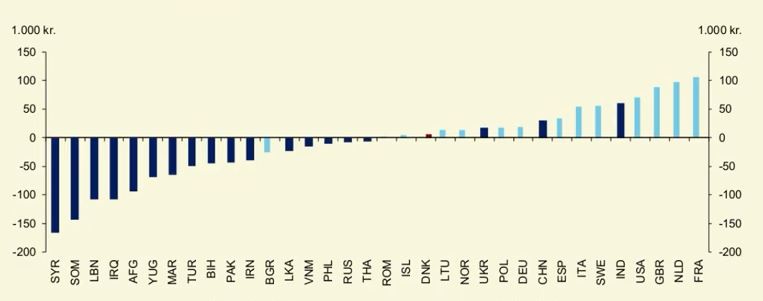

It is important to emphasize that the charts displayed averages: there are many different groups among both Western and non-Western immigrants. The following chart shows the net contributions of immigrants from different countries.

Dark blue bars: non-Western countries, light blue bars: Western countries.

The chart shows that, though non-Western, immigrants from India, China and the Ukraine have positive net contributions. Immigrants from India have, in fact, higher positive net contribution than Swedish, Italian or Spanish immigrants.

The following video shows Dr Kierkegaard’s results in more detail:

Will this cost be compensated for by the more indirect benefit of German economic growth as a result of the inflow of a potential work force and of additional consumers?

But immigration doesn’t only result in an increase of the population. There is also a negative trend: the emigration of Germans, mostly far better qualified than the immigrants of the recent mass migration wave. One motivation for emigration is the loss of quality of life as a result of the problems caused by mass immigration.