The Swedes are coming

Around 1000 A.D. Scandinavia saw momentous changes: the previously Viking-ruled areas organized themselves into kingdoms—Denmark, Norway and Sweden—and embraced Roman Catholic Christianity as religion.

Across the Gulf of Bothnia, Finland stayed behind in these developments. It was still populated by a number of tribe-like societies. “Finns” (suomalaiset) in the Southwest, Tavastians (hämäläiset) in the interior and Karelians further to the east. Nomadic Sami lived in the north. All had economies based on hunting, fishing, trapping animals for their fur and some agriculture. They spoke dialects of Finnish, a language belonging to the Finno-Ugric language family.

The religion of the Finnish remained mostly pagan; animism, ancestor worship and shamanism were likely practiced, though via trade contacts Christianity was also known.

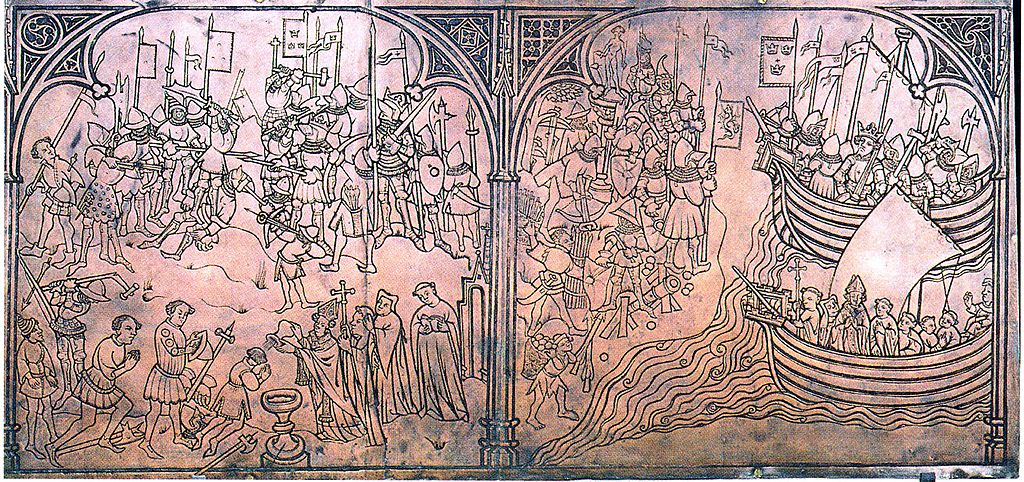

Already during the Viking times there was contact between the Swedish Vikings and Finland. Vikings traveled to Finland to trade and to raid and plunder. However, after the arrival of Christianity in Sweden, military expeditions against Finland soon took on a new, religious aspect.

Since the late 11th century the idea of crusades—religious wars in defense of Christianity—was “in the air”. In 1095 the First Crusade to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims was called by Pope Urban II. Within a few decades the original crusade idea broadened: crusades with the aim of converting “heathens” living in North-East Europe were approved by the church in 1147.

In about another 10 years, probably in 1157, the First Crusade in Finland was led by king Erik of Sweden, accompanied by Bishop Henry of Uppsala. After the king left the country Bishop Henry remained to organize the church in Finland. Additional, more organized expeditions and “crusades” followed, as the one by Bishop Thomas in 1240 and by Birger Jarl in around 1249. Christianity, together with Swedish rule, spread towards the East and South-East of Finland.

Under Swedish rule

During the same time as the Swedish conquest from the West was happening, the city state Novgorod—which, in contrast to the Swedes, had embraced the Greek Orthodox faith—was trying to conquer Finnish areas from the East. Clashes between the Swedes and the Novgorodians lasted until the Treaty of Pähkinäsaari in 1323 at which they agreed on a border between them. The border cut Finland in half, the southern and south-western part belonging to Sweden. Later the Swedish territory was extended to the North and further to the East, so that by the end of Swedish rule in Finland beginning of the 19th century most of current-day Finland was under Swedish rule.

Thus, by the mid-fourteenth century Swedish rule was firmly established in much of Finland. The native population was mostly peaceful and loyal to the Swedish kings, maybe partially because of the protection they hoped to receive against the enemy from the East: Novgorod and later Russia. The one exception was a peasant uprising in 1596/97 called the “War of the Clubs” (named like that because the peasants were using clubs as weapons).

After Sweden’s conquest of Finland, two main languages were spoken in Finland: dialects of Finnish and Swedish.

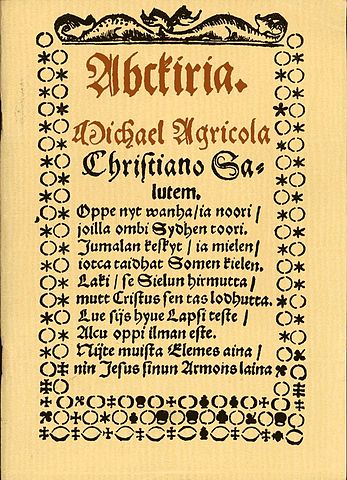

The peasantry and many of the clergy used Finnish while the language of the elites—the nobility and the officials—was Swedish. There was no written form of the Finnish language until the first book in Finnish was published: “ABC-book” (ABC-kiria), a primer of the Finnish language and catechism, by Bishop Mikael Agricola, in 1543.

In the 17th century Sweden became an increasingly centralized and autocratic state. There was a push to create a united, uniform population in every way possible. Religion was one of these ways, and it was actually achieved: Lutheran Christianity was the predominant religion in the whole Swedish Kingdom, including Finland.

Language, however, was a problem: in some parts of the Kingdom Swedish was not used as the main language. For example, in Southern Swedish provinces captured from Denmark during wars in the 17th century people talked Danish. And, of course, in Finland large segments of the population used Finnish in day-to-day life, instead of Swedish. The Danes were taught Swedish very quickly, and an attempt was made to increase the dominance of the Swedish language in Finland, too.

For example, E. Jutikkala and K. Pirinen write in their book A History of Finland (6th edition):

Finnish soldiers began to be taught commands in Swedish, and noncomissioned officers who were unable to speak Swedish were discharged … all Finnish-speaking congregations were ordered to hold church services in Swedish every third Sunday, in addition to the Finnish services (p. 194-195).

Riding on this wave of enforcing uniformity in the Swedish Kingdom, Professor Israel Nesselius (1667-1739) from the city of Turku, in West-Finland, went as far as suggesting a virtually total abandonment of the Finnish language and its replacement by the Swedish language. Finnish should be preserved only in a few backwoods areas, as a kind of open-air museum. But elsewhere, for example at courts of law, it should not be recognized. It should also be gradually replaced by Swedish in church services. In order to further promote this “swedicising” of the Finns, even saunas were to be abandoned.

The ideas of Nesselius were not implemented but it was not the last time that representatives of a ruling power tried to force usage of that power’s language onto the native Finnish population.

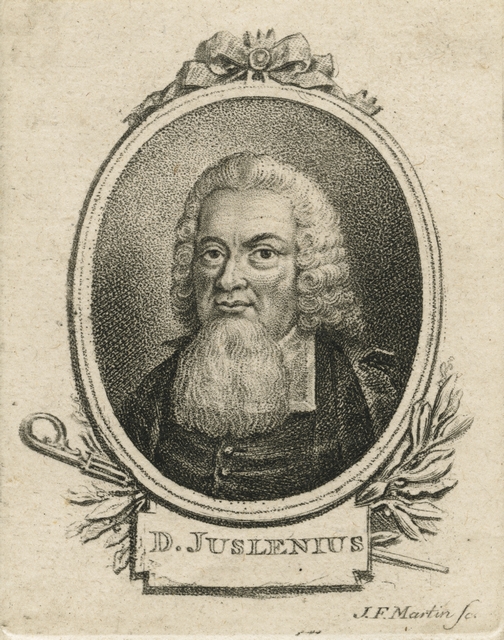

In any case, a backlash occurred: a “Fennophile” movement developed in the 18th century. Its representatives—e.g. professors Daniel Juslenius and Henrik Gabriel Porthan—enthusiastically promoted the study of everything Finnish. Juslenius, for example, phantastically claimed that the Greek and Roman civilizations originated in Finland and that Finnish was one of the languages which were spoken during the building of the Tower of Babel.

An interesting thing was that these “Fennophile” intellectuals were Swedish-speaking—understandably, as all the elites were still of Swedish origin. This phenomenon of Finnish causes driven forward by Swedish speakers was to repeat itself later in Finnish history.

Ideas of Finnish national independence start to emerge

At the core of the Fennophile movement was the idea that Finland had some things, in particular the Finnish language, which differentiated it from the mother country, Sweden. But the movement was apolitical—it didn’t result in calls for separation from Sweden.

However, in parallel to the Fennophile movement, ideas of a Finnish national sovereignty started to emerge. Some Swedish speaking politicians, like Georg Magnus Sprengtporten, a former colonel in the army, inspired by the Revolution of the British colonies in North America, started conspiratory talks with the Russians in the 1780’s, trying to convince them to support Finnish independence.

Later, during “Gustav III’s War”—named after Swedish King Gustav III—against the Russians in 1788, some officers in the Swedish-Finnish army mutinied and started negotiations with the Russians. Thus, there was clearly some dissatisfaction among the elites in Finland but it was totally separate from language issues. All of the people demanding separation from Sweden were Swedish speaking and, in fact, the Finnish speaking peasants remained loyal to the Swedish King.