Scientific and philosophical inquiry was non-existent among the Arab tribes at the time Muhammad started his new religion, Islam, beginning of the 7th century. By the 9th century, however, areas ruled by Islam became important centers of science and philosophy. This Islamic “Golden Age” lasted several hundred years, but then a decline followed, from which science under Islam never since recovered.

Meanwhile, Western European Christianity became a scientific backwater after the breakup of the Roman Empire in the 5th century. But then, it slowly started to develop and by the 13th century, the new Western European universities started teaching science and philosophy. Within a few hundred years, in the 16th and 17th century, the Scientific Revolution followed, unleashing an incomparable development of scientific knowledge in the West, continuing till today.

What explains these ups and downs in the history of science in Islam and in the West? How could the Arabs build up sophisticated science, lacking age-old foundations? And why did they lose it again? Why did science in Western Europe not go through the same decline as it did in Islam?

We are, in fact, confronted by the following questions:

- What explains the fast rise of science in the Islamic world—Islam’s “Golden Age”—starting around 750 A.D.?

- What explains the (relatively slow and delayed, as compared to the Islamic world) rise of science in Western European Christianity, starting in the 12th century?

- What explains the decline of science in the Islamic world, after a peak sometime between 800 and 1100 A.D.?

- What explains the continued rise of science in Western European Christianity, leading towards the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries and to modern science afterwards?

The focus in this article series will be on points 3 and 4, though the other points will be touched on as well. The reason for the focus is that these points are the most puzzling: how was it possible that science declined in the Muslim world after its impressive rise? And why didn’t the same happen in Europe, where science continued to rise?

These questions are not only puzzles for science historians: they have recently acquired an important political dimension having to do with Islam and Muslims and their role in current Western society. To assess this role, let’s consider first the Muslim population’s demographic trends in Europe.

Muslim demographic trends in Europe

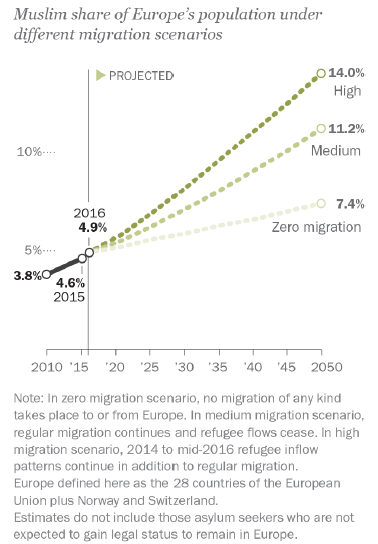

The number of Muslims in the West is growing. Currently the Muslim population of Europe is about 5% of the whole population. In 2017, the Pew Research Center presented a forecast about the development of the Muslim population in Europe. The figure below (on page 5 of the Pew Research Center’s Report) shows the three scenarios considered in the forecast:

It is already clear that the zero migration scenario is unrealistic, and it will not be considered here.

If a medium migration trend is assumed, the predicted percentage of Muslim population will more than double: it will be 11.2%. This will be concentrated in Western European countries like the UK (16.7%), Germany (10.8%) and France (17.4%). For the UK this will mean a more than 2.5-times increase of its Muslim population, as compared to 2016.

As also seen in the text below the figure above, the Pew Research Center’s article defined medium migration as follows:

Regular migration continues and refugee flows cease.

Europe’s growing Muslim population, Pew Research Center, p. 9.

It is already clear that a medium level of migration, as defined above, cannot be assumed, either: though the extremely high numbers of refugees registered in 2015 are now not reported, and — at least in Germany — there is a downwards trend of asylum applications, refugee flows haven’t ceased. Instead, they remain at high levels. The German Federal Center for Political Education writes this :

In 2018, 185,853 people applied for asylum in Germany. In the current year 2019, 46,477 initial or subsequent applications have so far [until 28.4.2019] been filed for asylum.

Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 26.4.2019

Thus, we have to assume higher than medium levels of migration.

Under a high migration assumption the European Muslim population will almost triple and will grow to 14% by 2050. These will not be evenly distributed. Instead, they will be concentrated in Western European countries like Sweden (30.6%), Germany (19.7%), France (18%) and the UK (17.2%).

Pew Research Center defines high migration level as follows:

2014 to mid-2016 refugee inflow patterns continue, in addition to regular migration.

Europe’s growing Muslim population, Pew Research Center, p. 10.

Given that in 2017 and 2018 refugee inflow decreased as compared to 2015 and 2016, high migration levels are not being sustained, either. Thus, the best assumption is a level between medium and high migration. But, whether medium or high migration is assumed, it will not make much difference for the Muslim population percentages for some European countries, for example for France (17.4% vs. 18%) and for the UK (16.7% vs. 17.2%), maybe because in these countries growth of the Muslim population is driven by factors other than refugee flows.

There are two additional things that should be considered: First, the Muslim population is not distributed evenly inside European countries. Instead, it tends to concentrate in larger cities like London, Birmingham, Paris, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main and Malmö. Thus, in these cities — the traditional historical, cultural, financial, economical and administrative centers of European countries — we can expect even higher Muslim population percentages than those predicted for the countries themselves.

Second, as the text underneath the Figure above shows, the scenarios don’t include asylum seekers who cannot expect to gain legal status to remain in Europe. This would be the majority of the asylum seekers. However, the developments of recent years — for example for Germany — show that very few of those whose application is rejected leave Europe. In Germany most of them receive a “tolerated” (geduldet) status and in all likelihood many or most of them will remain in Europe indefinitely.

Thus, the question is: how would the scenarios look like if Pew had included these asylum seekers, who, though their application is rejected, still remain in Europe? The authors of the Pew Report are aware of this issue (see p. 11 of the Report). They are also aware that including these asylum seekers in the scenarios would have had an effect on the predictions, but they don’t provide any detailed estimates of that effect. However, one can say with certainty that the result would be higher percentages of Muslim population for all three scenarios.

Whatever the exact numbers will be, it is already clear that Muslim influence in European societies will grow. This can be worrying, for different reasons. One reason for worry is that Western societies experience continuous problems with Muslim integration, meaning that Muslims have difficulties to adapt to attitudes and norms in Western societies and to leave attitudes and norms from their countries of origin behind.

In the context of the topic of this article, the reason to cause worry is the low intellectual development in most current Muslim societies.

Intellectual developments in Muslim society

Scientific development is at a low level in most Muslim societies. This is not a new development. Intellectual curiosity in topics outside the religious domain has been at low levels in Muslim society for a long time, as also illustrated by the video below.

Arab countries (all of which are overwhelmingly Muslim) translate far less books than countries in Europe. This is illustrated by the following fact, quoted from the UNDP Arab Human Development Report 2003:

In the Arab world … On average, only 4.4 translated books per million people were published in the first five years of the 1980s (less than one book per million people per year), while the corresponding rate in Hungary was 519 books per one million people and in Spain 920 books.

… a marked shortage of translations of basic books on philosophy, literature, sociology and the natural sciences is quite evident.

UNDP Arab Human Development Report 2003, p. 67.

This extremely small number of translated books is even more astonishing if one takes the large scale Greek-to-Arabic translation movement during the Abbasid caliphate into account.

One explanation for the small number of translated books (as compared to European countries) is the lack of intellectual interest in or maybe even rejection of what foreign countries can offer (though other causes, like the relatively low level of literacy in Arab countries or maybe the lack of people for sufficient language knowledge to do the translations could be operative as well).

Additional data presented in the UNDP Arab Human Development Report 2003 also point low levels of intellectual development in current Arab society. For example, though Arab countries constituted 5% of the world population in 2003, they only published 1.1% of the world’s books (UNDP Arab Human Development Report 2003, p. 77).

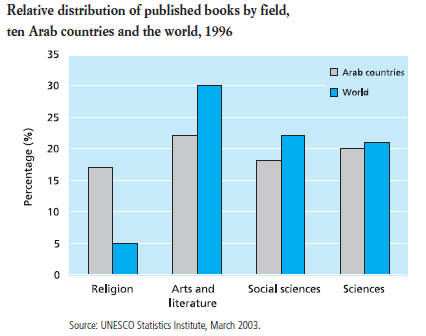

Looking at the topics of the books published in Arab countries, one sees a relative lack of interest in topics other than religion, as compared to the World average, and a corresponding increased interest in religion. The following Figure ( in UNDP Arab Human Development Report, 2003, p. 78) shows this:

Educational performance in Muslim society

Muslim minorities living in Europe show a consistently lower level of educational performance than the host populations or other minorities. The pattern is similar in countries outside of Europe. For example, the Indian web site Scroll.in writes:

Muslims comprise 14% of India’s population but account for 4.4% of students enrolled in higher education, according to the 2014-’15 All India Survey on Higher Education.

The situation has worsened over the last half century, according to the 2006 Sachar Committee, appointed to examine the social, economic and educational status of the Muslim community.

Given these signs of relatively low intellectual curiosity, increased interest in religiosity, and low educational performance, the question is: should we be afraid that the scientific and intellectual development in the secular societies of the West will suffer as the number of Muslims living in the West increases?

The political dimension

Many politicians in the West try to alleviate any such fear of Islam gaining influence. One example is the debate in Germany about whether “Islam belongs to Germany”, in which many high ranking German politicians like the Federal President and Chancellor Angela Merkel stated the affirmative.

Propagandists of Islam point to the “Golden Age” of Islam as a proof that Islam can actually be very friendly to scientific development. Some of these propagandists even maintain that science in Europe was in fact triggered by Muslim scientific achievements, as stated by Ahmed Salim, Producer and Director of 1001 Inventions, an “organisation that raises awareness of the creative golden age of Muslim civilisation”:

For a thousand years, scholars built on the ancient knowledge of the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, making breakthroughs that helped pave the way for the Renaissance. The discoveries made by men and women of different cultures working in Muslim civilization — from automatic machines and medical marvels to astronomical observations and inspiring architecture — have left their mark on the way we live today.

Though the “Golden Age” was a lot shorter than the “one thousand years” mentioned by Ahmed Salim, there is not much doubt that there was a period during the Middle Ages during which science and philosophy in Muslim-ruled areas was indeed the most advanced in the world.

Whether we should worry about the detrimental effects of increasing Muslim influence in Europe will have a lot to do with the question: which period is more typical for Muslim society: the “Golden Age” or the decline that followed it?

Was the “Golden Age” the “natural state” of Muslim society and was the decline enforced by some external causes, nothing to do with inherent features of that society?

Or was the “Golden Age” an aberration and was the decline which followed it caused by some inherent problematic features of Muslim culture and society?

If the former is true, then one can hope that the increasing number of Muslims living in the West will not necessarily have a detrimental effect on science in the West. Maybe one can even hope for a new intellectual “Golden Age” of Islam.

However, if the latter is the case, then the worries of many people who warn about the negative effects of Muslim immigration on science and education might well be justified.

This article series will try to answer these questions.