In Part 1 of this series the idea of “Great Replacement” is described and defined, relying on formulations by Renaud Camus (Camus, 2016) and others.

In this Part we start listing up the criticisms and counter-arguments against the “Great Replacement” concept, and we face these with empirical evidence.

The first kind of these criticisms attempts to downplay, minimize or relativize the demographic changes taking place in Europe which could amount to native Europeans becoming a minority in their own countries.

Downplaying the demographic reality of the “Great Replacement”

A recent article by Melissa Rossi is a good example of this approach. The article has a special focus on Martin Sellner, an Austrian Identitarian activist who states that a “Great Replacement” is indeed taking place.

Rossi argues against this, and writes:

[T]he Great Replacement theory goes entirely off the rails when proponents, such as Sellner’s group, assert, as they do on the Generation Identity website, that “Low birth rates of German and European people and simultaneous massive Muslim immigration will turn us into minorities in our own countries in a few decades,” leading to “the disappearance of Germans and Europeans in their own countries.”

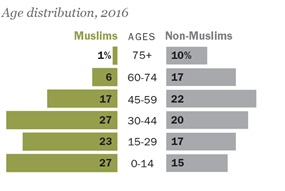

As evidence for her statement, Rossi quotes two academics. The first of them, demographer Landis MacKellar, wrote a review of Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission, criticizing the idea of a replacement of the French population by Muslims. Using data from the Pew Research Center from 2011, MacKellar predicts a Muslim population of 10% in France by 2030, a growth of 2.5% from 2010, when it was 7.5 %.

The other academic Rossi quotes, human geographer Hélène Ducros, “questions what data the [Identitarian] group is using to make such projections” based on the unreliability of population statistics in France. She doesn’t directly answer the demographic argument of the Identitarians. Instead, she tries to diminish the importance of the demographic change by saying:

“The reality is that Europe — in the largest sense, not just the EU — has always been a continent where people moved around a lot,” she says. “I would say that mobility, and thus intermixing, is what characterizes Europeans across time, not ethnicity.”

In addition to quoting these two academics, Rossi also refers to a report by the Pew Research Center from 2017 about Muslim demographics in Europe, and writes this:

A report from the Pew Research Center released in late 2017, “Europe’s Growing Muslim Population,” estimated the number of Muslims in Europe to be less than 5 percent. Even using the highest estimates for migration rates, the report estimated that in 2050, the number of Muslims continent-wide would be around 14 percent.

The rest of Rossi’s article doesn’t confront the demographic arguments of the Identitarians. Instead, she tries to draw parallels between them — and other people warning about the “Great Replacement” — on the one hand and Rightist extremists like the terrorist murderers Brenton Tarrant and Anders Breivik on the other.

This part of her article is not relevant for the current topic, thus we will not discuss it here – except by saying that Martin Sellner’s Identitarian movement is explicitly non-violent, that Sellner himself has, in several videos, very clearly distanced himself and his movement from murderers like Tarrant, and that neither the Identitarian movement nor Sellner were ever prosecuted for or convicted of any violent offense or for advocating violence against anyone.

In fact, despite the best efforts of Austrian state prosecutors, leading to a long court case against the Identitarian movement, and to many other harassments (including two raids on Sellner’s home, taking away all his video-making equipment, computers and mobile phones both times) not a single criminal offense could be found against the Identitarians or against Sellner. The Identitarians won the court case against them, on both the first and on the second instance.

The Austrian state prosecutor didn’t give up, and when it came out that Sellner received a donation from Brenton Tarrant (one year before the latter’s terrorist acts in New Zealand, at a time when there was no way to foresee Tarrant’s later terrorist act ), they started to investigate Sellner for terroristic connections, leading to all sorts of further harassments, including the freezing of bank accounts, another raid taking away all his equipment again, and so on.

On 3 December 2019 the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht) in Graz, Austria, has decided that all these measures taken by the state against Sellner were illegal, as they were based on ‘groundless speculations’.

Discussing the critics’ arguments

Here we shall discuss the criticisms against the demographic reality of the “Great Replacement”, as they appear in Melissa Rossi’s article. We shall examine the arguments made by Hélène Ducros, Landis MacKellar and by Melissa Rossi herself.

Hélène Ducros — Nothing to worry about: “Europe has always been a continent where people moved around a lot”

Let’s start with Rossi’s quoting Hélène Ducros, who, in essence, says: there is no need worrying about a “Great Replacement” in Europe, the demographic changes currently affecting Europe are nothing special, as Europe “has always been a continent where people moved around a lot”.

Note: we are not talking about military invasions here. Of these there was indeed many, and they were mostly actively resisted by the country which was invaded. We are talking about non-military, peaceful immigration, and in this sense Ducros’ argument is not true: people in Europe did not always move around “a lot”.

Taking Britain as an example, Douglas Murray writes this in his book The Strange Death of Europe, published in 2018:

Until the latter half of the last century, Britain had almost negligible levels of immigration … the mass movement of people was almost unknown. In fact immigration was so unknown that when it did happen people talked about it for centuries.

Murray, 2018, p. 30

Up to the 19th century there has been only one big wave of immigration into Britain: that of the Huguenots — French Protestants — in the late 17th century, 50,000 of whom entered Britain, fleeing persecution in France. This corresponded to about 0.8% of the population of Great Britain, which was then about 6.5 million.

There was much immigration from Ireland to England and to Scotland during the 19th century, many of the immigrants fleeing from the potato famine in Ireland during the 1840’s. At the very top of the immigration, about 4 % of the population of England, Scotland and Wales was Irish-born. After that, the proportion of the Irish-born decreased and by 1901 they constituted only 2 % of the population.

While the immigration of the Irish was indeed substantial, it was different from the immigration by Huguenots (and of the Jews, mentioned below): as Ireland was part of Great Britain at that time, immigration from Ireland was internal migration.

The other large wave of immigration during the 19th century was by Jews. Between 1881 and 1900 about 100,000 Jews immigrated to England from Russia and Poland, fleeing persecution.

The Jewish population increased further, both due to natural growth and to further immigration, in particular in the 1930’s, because of the Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe.

The demographic result of this Jewish immigration was that during the 60 years between 1880 and 1940 the Jewish population in Britain grew from 0.2 % to 0.79%, a 4 times growth. Since then, the Jewish population decreased again, and it was 0.46 % in 2001 (Lynn, 2011, p. 73-74).

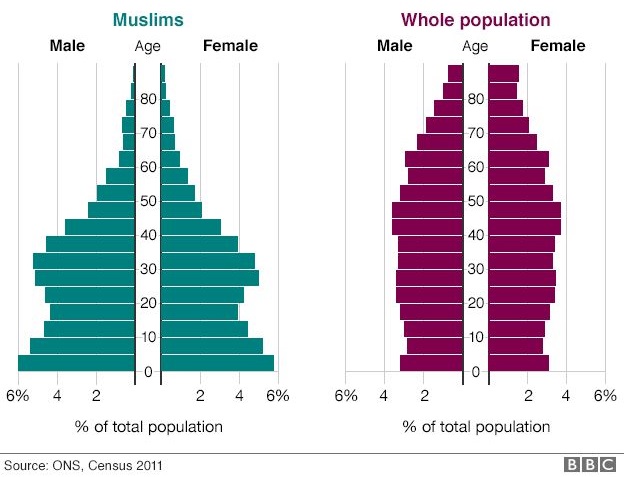

In comparison, the Muslim population in England and Wales grew during the 56 years between 1961 and 2017 from 0.11 % to 5.17%, making the Muslim population 47 times larger in 2017 than it was in 1961. This growth rate of an immigrant population is without precedent in British history.

And, of course, Muslims were not the only group that migrated to Britain over the last several decades. Many other immigrants came from non-Muslim parts of Africa, Asia and also from Europe.

In addition to the pace of migration, current migration patterns to the UK differ in two other respects from historical migration, too.

First, the three historical waves of immigration mentioned above — the Huguenots, the Irish and the Jews — were all Europeans with cultures, which, despite differences, were much more compatible with British culture than the culture of Muslim immigrants.

Second, during all three historical migration waves mentioned above, Britain’s native population was growing, during the 19th century even spectacularly. Thus, there was no danger at all that any of these three migration waves would threaten the native population’s majority. In contrast, during the current migration wave, Britain’s population is shrinking, at the same time as the immigrant populations are growing both due to immigration itself and to higher birth rates. This results in a continuously growing proportion of migrants in the population.

Figure 4. below illustrates this. It shows the disparity between the age structures of Muslims and of the whole population in England an in Wales, in 2011. The proportion of young people and children is far higher in the Muslim population, while the whole population has larger percentages of older people.

Age distribution of Muslims and the whole population in England and Wales, in 2011.

In summary, Hélène Ducros’ assessment that current migration is nothing special in European history is completely untrue.

Landis MacKellar — Nothing to worry about: “France has made it clear that it will not accept significant numbers of asylum seekers”

MacKellars article only concerns France. It would deserve a full refutation, but here we’ll only deal with the most relevant part.

MacKellar mentions a report about Muslim demographic from the Pew Research Center. This report, from 2011, predicts a Muslim population of 10 % for France in 2030, a growth of 2.5 % from 2010. Though MacKellar doesn’t attempt to make any projections beyond 2030, he confidently assures us that there is nothing to worry about, that “the statistical chances of a demographic remplacement from below are slim”.

MacKellar wrote his article in 2015, during the year of the refugee crisis. He is aware that the Pew Research estimate he is referring to was “pre-refugee-crisis”, as he writes, but this doesn’t make him re-evaluate the Pew Research predictions. Instead, he apparently bases his confidence that there is nothing to worry about on the fact that

France has made it clear that it will refuse to be the repository of significant numbers of asylum seekers.

MacKellar, 2015, p. 372

One wonders whether MacKellar is really so naive that he believes what he writes here. It is not “France” which makes any commitments about numbers of refugees to be accepted but the ruling government of France. These numbers can radically change any time when the government or its policies change, for example under pressure from the EU or from the UN (whose Global Compact for Migration France supported).

Melissa Rossi — Nothing to worry about: “the number of Muslims in Europe will be maximally 14 % in 2050”

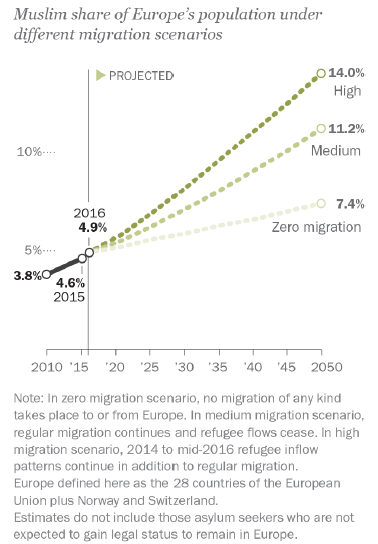

As mentioned above, Rossi refers to a report by Pew Research Center from 2017 with the title Europe’s growing Muslim Population. She correctly quotes the current overall Muslim population in Europe to be “less than 5 percent”. The figure mentioned in the report is in fact 4.9 %. She is also correct when she writes that according to Pew Research Center’s highest estimates for migration rates, the “the number of Muslims continent-wide would be around 14 percent” by 2050.

The Pew Research report defines “Europe” as the EU (plus Norway and Switzerland). 14 % of Europe’s population in 2050 will correspond to about 75.6 million people. An increase from 4.9 % to 14 % means that the Muslim population will almost triple during the 34 years between 2016 and 2050. This doesn’t seem to worry Rossi much, so let’s take a look at Pew Research Center’s predictions in more detail.

Figure 5. below (from the Pew Research Center’s Report, page 5) shows the three scenarios considered in the forecast:

Three scenarios of the development of Europe’s Muslim population (figure by the Pew Research Center).

It is already clear that the zero migration scenario is unrealistic, and it will not be considered here.

Medium migration is defined by the Pew Research Center as follows: regular migration continues and refugee flows cease. If this trend is assumed, the predicted percentage of Muslim population will more than double: it will be 11.2%. This will be concentrated in Western European countries like the UK (16.7%), Germany (10.8%) and France (17.4%). For the UK this will mean a more than 2.5-times increase of its Muslim population, as compared to 2016.

It is already clear that a medium level of migration, as defined above, is not realistic, either: though the extremely high numbers of refugees registered in 2015 are now not reported, and — at least in Germany — there is a downwards trend of asylum applications, refugee flows haven’t ceased. Instead, they remain at high levels. The German Federal Center for Political Education writes this in April 2019:

In 2018, 185,853 people applied for asylum in Germany. In the current year 2019, 46,477 initial or subsequent applications have so far [until 28.4.2019] been filed for asylum.

Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 26.4.2019

Thus, we have to assume higher than medium levels of migration.

High migration level is defined by the Pew Research Center as follows: 2014 to mid-2016 refugee inflow patterns continue, in addition to regular migration. Under this assumption the European Muslim population will almost triple and will grow to 14% by 2050.

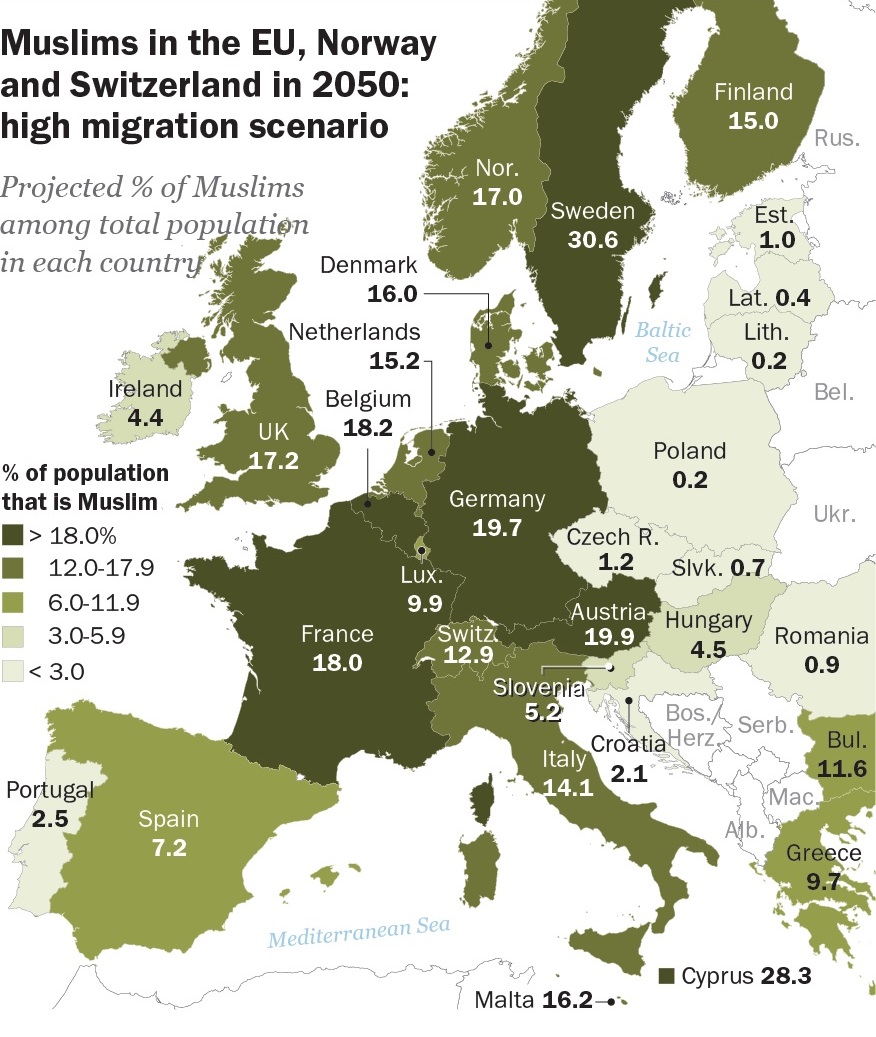

Figure 6. below is from the Pew Research Center’s report. It shows the percentages of the European Muslim population in 2050 for different countries, predicted by the Pew Research Center for the high migration scenario.

Prediction of the development of Muslim population in Europe in 2050,

high migration scenario (map by the Pew Research Center).

Whether medium or high migration is assumed, it will not make much difference for the Muslim population percentages for some European countries, for example for France (17.4% vs. 18%) and for the UK (16.7% vs. 17.2%), maybe because in these countries growth of the Muslim population is driven by factors other than refugee flows.

Given that in 2017 and 2018 refugee inflow decreased as compared to 2015 and 2016, the extremely high migration levels from those years are currently not observed. This would indicate that the correct assumption is higher than the medium but lower than the high migration scenario.

Note one important thing, though: as the text underneath Figure 5 shows, none of the scenarios include asylum seekers who cannot expect to gain legal status to remain in Europe. This would be the majority of the asylum seekers.

The developments of recent years — for example for Germany — show that very few of those whose asylum application is rejected leave Europe.

In Germany many of them receive a “tolerated” (geduldet) status. But even if it is attempted to deport them, this often fails because of many reasons: many of them have thrown away their identification papers, so that it is not possible to determine their real country of origin, others can’t be deported because leftist politicians insist that their countries are unsafe (even though Germans might go there for holidays), again others pretend to have medical problems which makes it impossible for them to fly in an airplane. Finally, many of these “refugees” simply disappear inside Germany, or they go to an other European country before they can be deported. This is from an article published by the German newspaper Die Welt in 2018:

According to the Central Register of Foreigners, about 618,000 people were living in the country at the turn of the year whose asylum application was finally rejected, most of them years ago. 78 percent of them are therefore already “legalized”; they are no longer obliged to leave.

Given this state of affairs, it is certain that all three of the Pew Research Center projections underestimate the number of Muslims in Europe in 2050 — in particular for Germany. Thus, it is probable that the most realistic assumption is near — and maybe even above — the high migration scenario.

There are two additional things that should be considered:

First, the Muslim population is not distributed evenly among European countries. The Muslim population in large Western European countries like Great Britain, France and Germany will be quite a lot higher than the 14 % average. In Sweden the number will be a lot higher than the average.

These countries are some of the economically, politically and culturally most important countries in Europe. Issues and problems related to the Muslim population in Europe already play a large part in the politics of these countries. It can be expected that 2 to 3 times larger Muslim populations — which these counties will have even according to the middle migration scenario — will increase the number of issues proportionally.

Second, the Muslim population is not distributed evenly inside European countries. Instead, it tends to concentrate in larger cities like London, Birmingham, Paris, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main and Malmö. Thus, in these cities — the traditional historical, cultural, financial, economical and administrative centers of European countries — we can expect even higher Muslim population percentages than those predicted for the countries themselves.

Germany as an example of demographic changes

Melissa Rossi‘s article which we discussed above focused on Muslim immigration into Europe. Though mass Muslim immigration is causing the most concern among Europeans, there is large scale immigration to Europe from many other parts of the world, too.

Here we shall describe recent demographic developments in Germany. Germany is an important country: it has the fourth largest economy in the world and the largest economy inside the EU. It is also the most populous country within the EU. Thus, whatever happens in Germany has wide ranging repercussions for the EU but also for the whole world.

Germany, with a largely homogeneous population after World War II, now has a population large segments of which have a “migration background” – many of whom are Muslims from Turkey, the Middle East, North Africa and Afghanistan. Many others have a background in Sub-Saharan Africa, in Asia or in Europe, e.g. in Poland.

According to the German Federal Bureau for Statistics, the number of inhabitants in 2007 with such a “migration background” was 15.3 million. Within nine years, by 2016, this number grew by 3.3 million, to 18.6 million.

In 2017 Reuters wrote this about the demographic situation in Germany:

The number of people with an immigrant background in Germany rose 8.5 percent to a record 18.6 million in 2016, largely due to an increase in refugees, the Federal Statistics Office said on Tuesday.

Just over a fifth of the population – 22.5 percent – were first or second generation immigrants with at least one parent born without German citizenship …

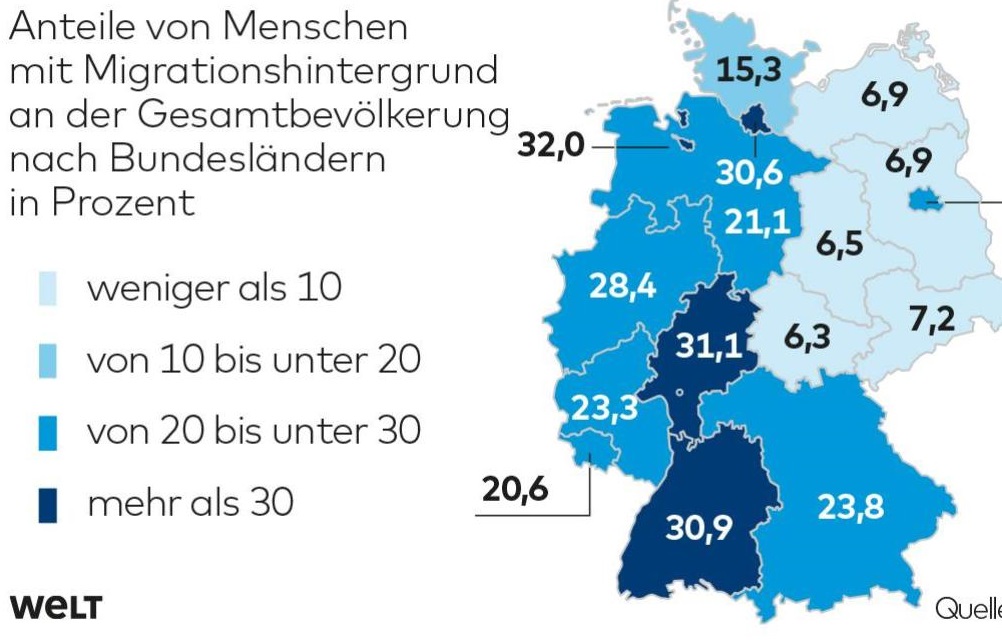

Thus, while, according to the most probable estimate, the Muslim population in Germany in 2050 will be around 20%, the population with migration background – Muslim and non-Muslim – was above 20% already in 2016.

The map below shows the percentages of inhabitants with migration background in German federal states in 2017.

(map by the German newspaper Die Welt)

People with a migration background tend to live in cities of the host countries and thus in big German cities the “migration background” proportion is greater than the average values shown in the map above. For example, in 2015 more than half of the inhabitants (51.2 %) in Frankfurt am Main had a “migration background”.

Note: the official German definition of “migration background” is that the person himself or at least one of his parents was born in a foreign country. In other words, third generation descendants of migrants, all of whose grandparents might have come from a foreign country, are not counted as having a “migration background”. If they are German citizens, as many are, they are counted simply as “Germans”. Many of them live in “ghetto”-like areas among people with a similar ethnic and cultural background as themselves and have little connection to German culture, German traditions or to German society in general.

Thus, this definition of “migration background” – and the map above – understates the demographic and cultural changes ongoing in Germany.

The proportion of people with “migration background” will definitely grow further. The current percentage of children with migration background opens a window into Germany’s demographic future.

According to the German Federal Center for Political Education,

In Germany there were around 13.4 million children in 2017, of whom 4.9 million had a migrant background (36%). In the younger age groups, this proportion was highest: Among children under 3 years, the proportion was 39%.

Within 20 to 30 years, these under 3 years old children with migration background will constitute almost 40 % of the adults in the most fertile age group of the population. Given current trends, they will have more children than the rest of the population, thus further increasing the birth gap between the indigenous German population and of those with migration background.

In big German cities – the important centers of economic, political and cultural life in Germany – the proportion of children with “migration background” is even higher than the numbers above, as published in an article of the newspaper Der Tagesspiegel in 2018:

In Frankfurt am Main … 55 % in the age group 1 to 6 years have no German roots. … In other major cities, such as Cologne, Munich and Stuttgart, the proportion of the under-six-year-old children with migration background is more than 50 %. In Berlin and Hamburg, it is just under 48 and 44 %.

Summary

Is Rossi correct, when she ridicules the Identitarians’ statement that “low birth rates of German and European people and simultaneous massive Muslim immigration will turn us into minorities in our own countries in a few decades”?

It depends on what a few decades mean. If it means three decades from now (which is apparently how Rossi interprets “a few decades”), several important European countries and cities will probably change beyond recognition, but a “Great Replacement” by Muslims will not happen by then.

But what if we are talking about four, five or six decades? At the growth rate of the high (and even of the medium) migration scenario, a majority Muslim population in Europe — at least in countries like Sweden, Germany, France and Great Britain — is very well possible within five or six decades, if current immigration policies continue. As there are many supporters for these policies both at the level of individual European countries, at the EU, and at the UN, it is very well possible that these policies will continue and will even intensify.

Also, what if we are talking about the population with a migration background in general – not just about the Muslim population? Though Muslim immigration causes the biggest concerns in Europe, there is lots of immigration from non-Islamic regions of the world, too, for example from Sub-Saharan Africa and from parts of Asia. As the previous chapter about Germany shows, already now, in 2019, young children with migration background constitute around 40% of all children in that age group. It seems almost certain that within a few decades people with migration background will be in the majority in that country.

Another important factor that should be considered is the projected growth of the population in Africa and in the Middle East — the two main sources of immigration to Europe. By 2050 Africa’s population is expected to almost double, from currently 1.22 billion to 2.3 billion. The population of the Middle East is expected to grow from the current 411 million to 678 million in 2050. Already now there is a huge migration pressure from these regions to Europe. Given the above numbers, we can expect this pressure only to grow.

Last but not least, the Pew Research Center report from 2017 acknowledges (on page 43) the many uncertainties involved in projecting the growth of Muslim demographics in Europe. This, together with the fact that demographic changes of the kind discussed here are practically irreversible, gives further justification for concerns about a “Great Replacement”.

Thus, relying on assurances by Rossi, Ducros and MacKellar that there is nothing to worry about, that, as MacKellar states, the idea of a “Great Replacement” is “easily discredited”, would be foolish and dangerous for anyone who would like to preserve the identity of European countries into the future.

Our conclusion is this: a “Great Replacement” is indeed happening and if policies as practiced in European countries remain as they are now, European indigenous populations will become minorities in many places in Europe. European culture will go the same way: it will be embraced by a minority only.

But the next question is: how should this demographic fact be judged? Is it good or bad – and why? This is the topic of the next Parts of this series.

Literature

Camus, R. (2016). Revolte gegen den Grossen Austausch. Schnellroda: Antaios.

Lynn, R. (2911). The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence and Achievement. Washington Summit Publishers.

MacKellar, L. (2015). La République islamique de France? A Review Essay. Population and Development Review, 42(2), 368-375.

Murray, D. (2018). The strange death of Europe. London:Bloomsbury.

To be continued.